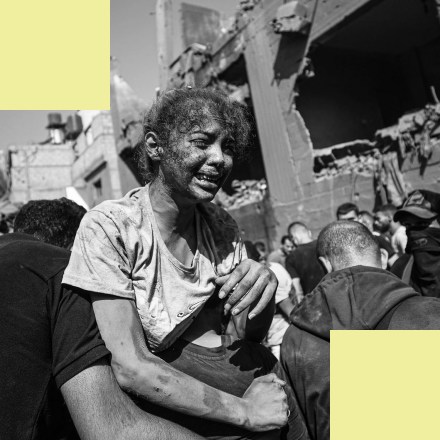

Palestinians flee Gaza City and other parts of northern Gaza to the southern areas amid Israel’s ongoing bombardment of the region, on Nov. 11, 2023.

It was Thursday night when we started to negotiate. Do we need to evacuate to the south or not? The F-16s did not leave the sky, the bombing did not stop, the live ammunition was very close. The sky was foggy, gas bombs and white phosphorus filled the sky. It was hard for us to even breathe.

Our job is to document the war, to let the world know what is happening. How could we leave? For hours, we asked the question. I had a headache from overthinking.

“What if they kill us? What if they arrest us?” one guy asked.

“I am not leaving, I prefer dying here,” another said.

“We should leave, we have kids and families.”

“We did everything we can. We reported everything.”

Despite the sound of the bombs, I urged myself to sleep. I wondered if this might be my last night in the office, my last night in the city.

Our job is to document the war, to let the world know what is happening. How could we leave?

We had evacuated from the office three times in 30 days. We evacuated from the office to Roots Hotel, but journalists there were targeted, so we evacuated to Al Shifa Hospital. After the threats the hospital received, we chose to risk it and go back to our three-room office in the Al Rimal area, near Al Saraya.

I used to live on a mat on the floor in the office. I had a private bathroom.

The 11th floor office had the best view of Gaza. It was home when we were displaced. It was our tiny home.

I slept as my colleagues were still debating.

It was 6:30 when my colleague Ali woke me up. “Get ready, we are leaving,” he said hurriedly.

“Go where? Nowhere,” I told him. “Let’s find another place to go. I do not want to leave.”

“Hind, yalla, no time to negotiate, we do not have a lot of time,” he stressed while he was packing his cameras in his backpack.

I stood up from the mat. Everyone was packing, searching for their stuff. I realized that I do have ADHD, as I’ve always suspected, because I had no idea where to start.

It was less of a problem because I barely have clothes anyway — a couple of dirty sweaters, my laptop, and my camera. I have been displaced since October 9.

I grabbed my bag and hurried with Ali to pick up his injured mom and my cousin. Ali drove so fast. We parked away from the Al Shifa entrance. The entrance to a hospital has become a danger zone, with several having been bombed recently.

We started walking so fast trying to enter the hospital. It was crowded, people were rushing out.

We started pushing people. It took us more than 10 minutes to reach the building from the entrance, a distance that normally takes just a minute or less to cross.

I went to find my cousin, Sara. She works as a surgeon and has been in Al Shifa hospital since day one. Ali went to get his injured mom and sister.

I started knocking on the door. “Sara, open the door. It’s me, Hind.”

I kept knocking for three minutes until another doctor opened the door. Sara was sleeping.

I woke her. “Hurry up, we are leaving,” I told her.

She gave no reaction. She began packing her clothes.

Ali took his mother in a wheelchair. I took my cousin with a couple of doctors.

My cousin Dr. Sara waiting during the exodus on Nov. 10, 2023, in Gaza.

The corridors were becoming empty, everyone in a rush. Even patients were evacuating.

By now, we were far too many to fit in the car, so we began to walk. We walked with thousands of other civilians. I even saw a hospital bed being pushed along the way.

Children, people in wheelchairs, the elderly, babies — everyone was carrying their backpacks, pillows, and mats.

We waited at the intersection for 40 minutes until Ali met us. Together, we walked.

I studied the looks on people’s faces. Terrified, they were holding white flags.

A truck that normally carried cows was packed with people. Another truck that used to transport gas canisters took people to the south.

People crying, angry, sad, eyes filled with fear.

My emotions were blocked. All I could think was that I do not want to leave, that it was wrong to leave, that I must not leave.

Everything was destroyed. Even the streets were damaged and destroyed. My eyes were trying to document everything, I tried my best to capture everything in my eyes. I wanted to cry my tears out, but I held them inside me.

It’s not time to cry, I will cry later, I told myself.

We started walking from the “Doula Square” — the launching point.

We found donkey carts. They called out that they would take us as far as the Israeli tanks.

We reserved two carts. The owner was in a hurry; he charged us 20 NIS — around $5 — for a 10-minute donkey ride. Some could not afford it, so they walked on foot.

I saw people carrying cats, carrying their birds in their cage, holding their bags, taking as much as they could.

We reached the area scraped flat by bulldozers. I saw one bulldozer, two tanks, and a dozen soldiers.

This was the first time many people in Gaza — especially kids — would see a tank or an Israeli soldier.

The owner of the donkey carts told us that this was as far as he could take us. All the people started holding out their green IDs, raised their hands and their white flags. Everyone was terrified. This was the first time many people in Gaza — especially kids — would see a tank or an Israeli soldier.

I saw Israeli soldiers in 2016 when I left the Gaza Strip through Erez, the fortified border in the north. I was not scared.

We were still walking. I was holding two bags, one on each shoulder. Ali’s injured sister was leaning on me all the way. She got shrapnel in her leg when the Israelis targeted the Al Shifa hospital entrance.

As I was walking with the crowd, I was looking toward the ground. I saw baby blankets, baby slippers. I saw clothes, toys, bags. I’m sure people were too scared to go back and pick up the stuff they dropped.

We walked over dead, decomposing bodies.

We were thousands of us pushing each other on this one-way road. We wanted this to end. To our left was a tank and soldiers holding their rifles, watching us through binoculars on a sand hill. To our right were four soldiers standing in front a bombed-out building, posing and taking selfies on the rubble.

Our group was stopped more than four times (for no reason) — and let go for no reason.

As we approached the soldiers, I saw a naked man standing in front of the sand hill alongside three other men with their heads down.

Another man with a yellow five-gallon water jug and a blond child were called over by the soldiers. They asked the small boy to step closer without his father. The boy was terrified. Those of us walking past worried the boy would be taken.

The soldier told him there was nothing wrong, he just liked blond kids.

We kept walking. As we walked, pushing each other, we saw bombed cars and dead bodies inside the cars.

Flies filled the cars, feasting on the blood and the bodies inside.

A newborn in front of me was crying. The mom was trying to make food for her as we were walking. She started nursing her without stopping the walk. Another mom was pulling her kids in their baby seats with a rope.

A man pushed an injured woman in her wheelchair. It kept getting stuck in the sand.

We kept walking, stopping, then walking, the soldiers a constant threat.

It felt like years of walking, though it was only hours. It was packed, and we constantly looked between the crowds for each other. On the other side were people who were already in the south and came to pick us up. People in the south were searching for us, for people coming from the city. Everyone was tired. Everyone was thirsty.

I had lost my cousin in the crowd of thousands, but found her at the end. She was crying, her leg had given out. She was in intense pain. We helped her keep moving until we could find a car.

I can’t describe the sadness. We escaped from being killed or injured, but I did not want to leave — and did not want to leave the city.

As we walked closer to where the cars were stationed, people started distributing water to us. They told us we were welcome and that their homes were open to us.

We were so tired. I could not feel my shoulders or my legs.

Everyone was happy we evacuated; everyone was hugging us. We had safely made it.

But I did not feel the same. A piece of my heart was left in the city, and I may never be able to go back to get it. It is impossible for me to imagine I abandoned my father’s house, left it alone. He built that home with his own hands, and when he died in 2012, it stayed with the family. Our house in my family is something so precious to us. We do not know if our house is still standing or not, but we know that we are not in it.

Fifteen minutes after we arrived, the people walking behind us were bombed.