Michael and Christie Brown resisted putting a barrier around their beloved desert home for years, but the nights were getting too dangerous. It was a question of safety. They needed a fence.

The Browns live 10 miles north of the U.S.-Mexico border, on the southeastern edge of Sierra Vista, in Cochise County, Arizona. Like many of their neighbors at the foot of the rugged Huachuca Mountains, the Browns’s worry was javelinas, tenacious borderland omnivores often mistaken for wild pigs. Their dogs had been attacked. Their garden was in peril. Javelina damage keeps the Browns up at night. A purported wave of migrants laying siege to their community does not.

In late October, Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey began unloading thousands of shipping containers on the border in the Coronado National Forest to thwart a supposed “invasion” on the Browns’ doorstep. Topped with concertina wire and welded together, the nearly 9,000-pound boxes would be stacked two high on land where the retirees chop wood every winter, where they took their sons hiking and camping as kids, and where they still hike and camp to this day. In the early 2000s, they saw evidence of heavy migration through the area — discarded desert clothes, empty water jugs, trash — but it hadn’t been like that in more than a decade.

On October 26, two days after Ducey’s project began, the Browns got in their truck and set off to see the shipping containers for themselves. They descended a rocky road east of the picturesque San Rafael Valley, then turned south toward Mexico. As they neared the border, they were stopped at an ad hoc checkpoint. A bald man, dressed in black with body armor and reflective sunglasses, approached. He wore no insignia and refused to say who he worked for. Michael asked if he could drive up to the containers and take some photos. The guard said he could not. Michael asked him why.

“I’m not answering any more questions, sir,” the guard replied.

The scene was as horrifying as anything the Browns could have imagined. Heavy-duty pickups were ripping down the dirt road hauling in shipping containers on trailers. The containers were then transferred onto a large military truck that raced down the road running parallel to the border, blaring a loud horn as it passed. At the end of the line, the containers were wrapped in a thick chain and hoisted by backhoes. Swinging precariously through the air, they were plopped in the dirt, then shoved into place with a forklift. The clanking and screeching of metal on metal filled the otherwise quiet landscape. The grinding of the heavy vehicles on the desert soil enveloped the entire area in a thick cloud of fine dust.

Christie was incensed, telling the guard that she would walk to the containers. “This is a dangerous area, ma’am,” the man said.

“This is our national land,” Christie said.

The guard cocked his head to the side, like he was schooling a child. “This is also the state of Arizona,” he said. “Are you a federal employee?”

Michael interjected: “I was.”

Michael, now 67, had lived in the area for nearly half a century and knew as much about border walls as anyone. Serving in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for two decades, he oversaw the construction of Border Patrol stations in Naco and Douglas. In 2007, he oversaw installation of the first federally contracted “pedestrian fencing” in Arizona. He continued to oversee wall construction across the southwest into the Trump years, before retiring in the spring of 2021.

Looking out across the landscape, Michael Brown saw a reckless operation that he would have shut down in a heartbeat. He decided to take a walk through the brush, snapping photos of birds while taking in evidence of the environmental damage. Christie waited back in the truck with their dog, Izzy. A man parked nearby and trained a pair of binoculars on Christie. He watched her until Michael returned and continued watching as the couple drove away.

An hour later, the Browns were back home when the doorbell rang. Michael opened the door to find two armed men in body armor, a pair of unmarked vehicles behind them. Unlike the guard at Coronado, they wore identifiable insignia. This was Cochise County Sheriff Mark Dannels’s heavily subsidized and much-advertised border strike force.

The deputies told Michael they’d received a complaint that a truck like his, carrying four suspicious men, was spotted outside a hotel where the governor’s contractors were staying. The contractors had told police that they were frightened. Michael explained that he and Christie had simply gone to see the container wall. He showed the deputies cellphone video of their interaction with the guard. A third unmarked vehicle pulled into his driveway. Before long, the deputies’ demeanor softened, they turned friendly and appeared satisfied. As they left, one of the men remarked to Michael that the governor’s wall was a “sensitive political situation.”

“I know the contractors at the border took down my license plate and called them,” Michael told me a month later, over coffee in his kitchen. “I don’t understand why.” While some would be unnerved, he was mostly perplexed. Anyway, he and Christie now had bigger things to worry about.

Since their visit, Ducey had cut across miles of pristine desert. Federal authorities had told the governor that his project was illegal, but were doing nothing to stop it. The Browns were shocked. “The Forest Service is mandated to preserve and to protect our national lands,” Michael said. In the face of inaction, the Browns were left with one choice: gather as many friends, neighbors, and allies as they could and stop the governor themselves. President Joe Biden greets Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey after arriving on Air Force One, on Dec. 6, 2022, at Luke Air Force Base in Maricopa County, Ariz.

For seven weeks, the Biden administration has watched Arizona’s governor engage in a pattern of brazen lawbreaking along the border, destroying public lands that the administration is sworn to protect, and done nothing to stop him. Ducey, who’s leaving office in January, has committed at least $95 million to this effort, but the Republican governor’s renegade campaign could end up costing Arizonans far more.

Ducey’s Democratic successor, Gov.-elect Katie Hobbs, has said she will stop adding containers to the wall. She has not, however, committed to taking the existing structures down. If Hobbs does take the containers down, it could cost as much or more than it did to put them in. If she doesn’t, it will mean the collapse of a remarkable binational ecosystem, one of the last places in the U.S. where jaguars still roam, and the death of a stunning Sonoran Desert landscape set aside for all to enjoy.

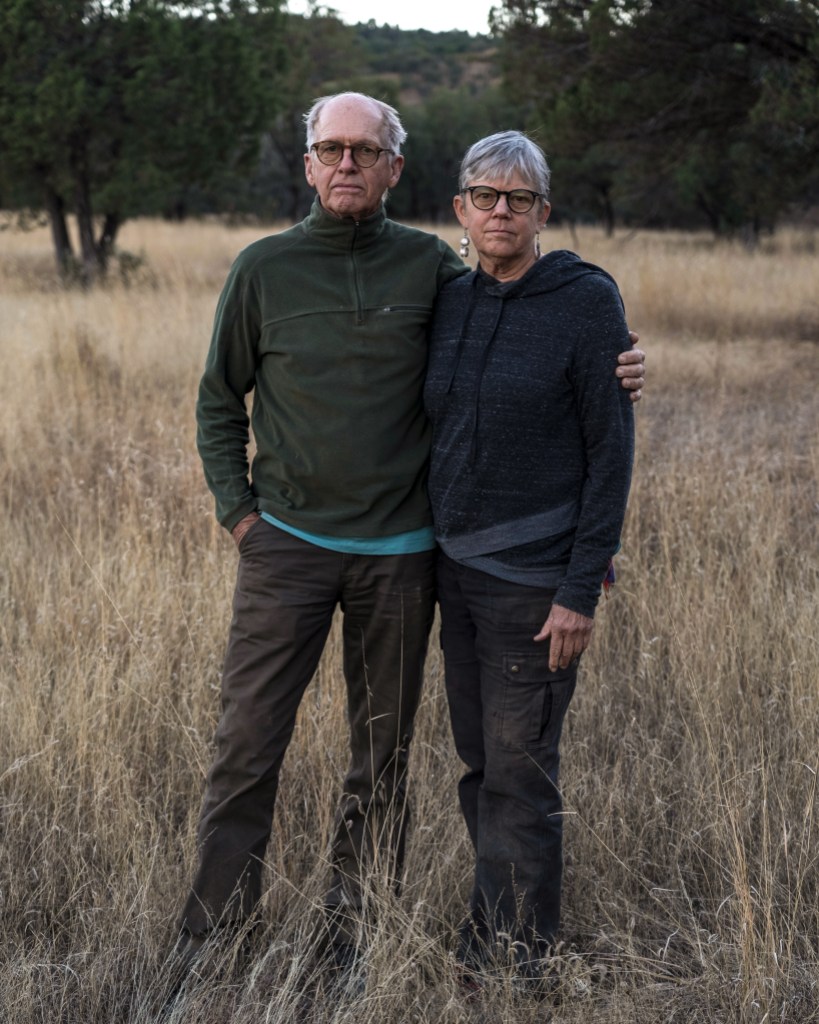

The story of Arizona’s wall of shipping containers is a story about immigration and conservation, of public lands and insurrection, but as the weeks went by, it turned into something more. In the shadow of the governor’s wall, a roughly four-mile stretch of the U.S.-Mexico border became the setting for a remarkable and unlikely story of everyday people who, with no one to count on but each other, stood up against the most powerful lawmaker in their state and won. Michael and Christie Brown near the shipping container wall on the U.S.-Mexico border in the Coronado National Forest in Arizona, on Nov. 29, 2022.

While the Browns were taking in their first ground-level glimpses of Ducey’s wall on October 26, Russ McSpadden was monitoring the scene from above.

McSpadden works for the Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity, where he documents threats to the unique ecosystems of the Sonoran Desert. On social media, he intersperses viral videos of destructive border wall construction with equally popular videos of borderland wildlife. His encyclopedic knowledge of Arizona’s backcountry is matched by his passion for the animals that live there. From iridescent bugs to lightning-fast pronghorn, McSpadden loves them all, but one borderland resident stands above the others: el tigre de la frontera, the jaguar.

McSpadden’s employer has been central in the fight to return the big cats to their historic range across the American Southwest. In 1994, the group filed a lawsuit that led to the inclusion of jaguars on the Endangered Species List. Today, McSpadden is part of a constellation of advocates and biologists who monitor the ultra-elusive predators as they pass back and forth across the border. He is one of the few people alive who has managed to capture a jaguar on a game camera in the Arizona borderlands — not once, but twice.

As part of the center’s legal efforts, the federal government was forced to designate 1,194 square miles in Arizona and New Mexico as critical jaguar habitat in 2014, limiting the kinds of activity permitted there. That habitat included land on the western slope of the Huachuca Mountains in the Coronado National Forest, where Ducey began dropping his containers on October 24.

When the container project began, McSpadden was in a single-engine airplane flying low over the border. His phone rang. Robin Silver, a co-founder of the center, was on the line. He told McSpadden to get to Coronado right away. Tell the pilot to land, he said, or better yet, fly to the installation site.

It wasn’t possible. I happened to be in the air with McSpadden that day. For more than a month, we had both been trying to confirm rumors that Ducey was preparing a mass deployment of containers somewhere outside Nogales, Arizona, likely in Coronado National Forest. Hundreds of the metal boxes had been stored at an unused armory in the border city then quietly disappeared. The governor’s office was being cagey, confirming that Ducey was eyeing locations but refusing to confirm where. McSpadden and I took a tour with EcoFlight, a company that provides aerial tours to environmental advocates and journalists, to scout for signs of activity in the Pajarito Mountains. By the time we touched back down in Tucson, it was clear we should have been flying further east. Russ McSpadden, Southwest Conservation Advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity, scans the border for signs of new wall installation. October 24, 2022.

Like others who documented southern Arizona’s environmental destruction under President Donald Trump — compiling evidence of the Department of Homeland Security blowing up national monuments and depleting a sacred Native American oasis — McSpadden was still recovering. He hadn’t been on the border in a professional capacity in a year. Ducey’s threat to jaguars drew him back out.

Two days after our flight, I climbed into McSpadden’s work truck. Setting off in the morning, we pulled into the Coronado National Memorial before noon, then hiked south along a ridge with a commanding view of the landscape below.

Though we were miles from the site, the noise of Ducey’s project echoed through the valley. One after another, pickups pulling containers came rumbling down the Forest Service road that leads to the border. Plumes of dust curled above them. McSpadden set his backpack in the grass and unloaded a drone. I leaned against a wire fence and squinted into the valley. In just two days, Ducey’s contractors had fashioned a shipping container fort to serve as their base of operations. Armed guards waited at the entrance. McSpadden nicknamed it the “OK Corral.”

The drone zipped into the air and was out of sight within seconds. We spent two hours on the ridge watching Ducey’s trucks transform wilderness into junkyard. Trump’s wall-building was jarring for anyone who saw it up close, but this ramshackle operation was something else entirely.

On the Friday before Ducey’s container installation began, a team of private attorneys working on behalf of the governor filed a lawsuit in federal court against the U.S. Forest Service, the Bureau of Reclamation, and top officials at the agencies, along with the secretary of the Department of Agriculture. The lawsuit followed more than a month of warnings from federal officials that the project Ducey was cooking up was unauthorized and thus, illegal.

On September 16, Coronado National Forest officials received a request from the Arizona Division of Emergency Management seeking “authorization to place barriers on National Forest land in all areas that currently have gaps in the federal wall.” The Department of Emergency and Military Affairs, or DEMA, manages a $335 million “Border Security Fund” that the Republican-controlled legislature approved in 2021. The disbursements have been controversial, with the governor’s emergency managers distributing more cash to Republican-led counties and sheriffs — including Cochise County and Dannels, its sheriff — than their Democratic counterparts.

With DEMA showing no sign of plans to abide by the process for the authorization of a massive construction project on federal land, the Forest Service denied Ducey’s request. On October 6, Kerwin Dewberry, Coronado’s forest supervisor, sent a letter to Maj. Gen. Kerry L. Muehlenbeck, the director of DEMA, reporting the sighting of dozens of shipping containers, construction equipment, and private security personal on federal land. “The Forest Service did not authorize this occupancy and use,” he wrote. Muehlenbeck fired back, pointing to a state of emergency Ducey declared in August: “Due to the lack of response and pursuant to the directive by Governor Ducey, work will commence to close the referenced gap to ensure the safety of Arizona citizens.” The response prompted an escalation from the Forest Service, with the chief of the agency’s southwest region reiterating that the governor’s project was unlawful.

In his complaint two weeks later, Ducey focused on the so-called Roosevelt Reservation. In photographs, it’s that flattened land that runs parallel to the border wall. Former President Theodore Roosevelt set aside this 60-foot-wide roadway as federal land in 1907, five years before Arizona became a state, so that the U.S. government could forever have an unimpeded view into Mexico.

For 115 years, the agreement that the easement is federal property has been a staple of borderlands jurisprudence. Ducey, however, presented the novel argument that Roosevelt’s declaration lacked authority and the state had jurisdiction over the land, particularly in times of emergency and cases of invasion; Ducey declared that both were present in Arizona in August. Under President Joe Biden, the federal government abdicated its obligation to provide security by opening the border to a criminal invasion of drugs and foreigners, the governor alleged. Arizona had the right to defend itself by filling gaps in the border wall that Trump left behind. (The Biden administration was already in the process of filling those gaps.)

Ducey’s reading of the law would grant border governors unprecedented power to sidestep federal statutes that have governed public lands for generations. In his view, he was both empowered and obligated to disregard those time-consuming processes. His lawsuit called on the court to agree.

Until a judge rules otherwise, Ducey has demonstrated every intent to keep doing what he’s doing. The Department of Justice has filed a motion to dismiss his suit.

Ducey selected AshBritt, a Florida-based disaster response company with significant ties to the Republican Party, for the Coronado project. In 2018, the company made a half-million-dollar donation to a Trump Super PAC, in violation of prohibitions against federal contractor political contributions. The firm’s CEO paid a hefty Federal Election Commission fine. Trump’s former White House counsel, Donald McGahn, negotiated the settlement.

The Center for Biological Diversity quickly filed suit against Ducey, citing the threat to jaguar habitat under the Endangered Species Act, but there was a catch. The landmark environmental law gives defendants nearly two months to change allegedly bad behavior before any enforcement activity can commence. That meant nothing was happening right away. So in addition to that suit, the organization also intervened in Ducey’s lawsuit as a defendant. If the feds wouldn’t defend the land, Robin Silver, the group’s co-founder, told me, the Center for Biological Diversity would.

“What I saw was shocking and heartbreaking.”

McSpadden submitted a declaration in the case. Though Ducey had asserted authority over the Roosevelt Reservation, McSpadden detailed how the governor was, in fact, widening the longstanding federal easement. Describing our visit to the site the previous month, he testified: “What I saw was shocking and heartbreaking.”

McSpadden’s declaration was filed November 1, seven days before the midterm elections. Silver was sending his images from the field directly to Biden’s top land managers, including the defendants in Ducey’s lawsuit and Interior Secretary Deb Haaland. With four decades of experience suing the federal government, often successfully, Silver’s connections in Washington run deep. He demanded that the feds do their job and stop Ducey’s lawbreaking. The message he got back was clear: Wait until the elections are over.

Less than 24 hours after Arizona’s polls closed on November 8, McSpadden and I were on the ground in Coronado. This time, instead of watching from the ridge, we drove directly to the site.

After walking the length of the wall, we cut through the OK Corral on the way to our vehicles. A gaggle of contractors in the makeshift fort exploded, shouting that we couldn’t be there and that they would call the sheriff. One of the men yelled out that he had already sent two people to the hospital that day and would happily send two more. As we continued, a private security guard with a sidearm approached and told us that the area was “very dangerous.” McSpadden responded that we were on Forest Service land, and the governor’s contractors were free to leave.

Up close, the scene had a Mad Max feel. Swirling dust. A wall of containers crowned with razor wire. Trees snapped, trampled, and shoved into mangled heaps. The contractors had laid down more than a mile of boxes since our last visit. The desert washes that provide runoff for monsoon rains were now blocked. Most startling of all were the bus-sized military vehicles racing down the narrow Roosevelt Reservation road. It felt unsafe for all living things in the area, including the workers.

Sprawled out beyond the northwestern edge of Sierra Vista, the Fort Huachuca Army base is the biggest employer in Cochise County’s most populous city. Established in 1877, the fort began as an outpost in the U.S. campaign to destroy the Chiricahua Apache. Today it’s a hub of drone, intelligence, and electronic warfare operations. Its motto: “From sabres to satellites.”

Michael Brown was a young carpenter when he landed a job on the base in the early 1980s. He had fallen in love with the jagged mountains and golden grasslands of the San Rafael Valley after a Christmas visit in 1975. Brown’s work on the base led to a job with the Army Corps of Engineers, which turned into a 20-year career of inspecting and managing border job sites. He insists the structures he built for the Bush and Obama administrations were “fences,” not “walls.” There’s a meaningful distinction, Brown argues: Fences can be seen through, walls cannot. “Border Patrol agents do not like walls,” he said. “They want to be able to see into Mexico.”

“I can proudly say that I had no part of the Trump-era stuff. To me, that was not done for security. It was for racism.”

Brown has complicated feelings about his old line of work. “I do have a history that I’m not proud of,” he told me the first time we spoke. From the beginning, he said, he questioned the border wall projects — “It just didn’t feel right,” he said — but still he worked on them. Brown’s last wall was an Obama-era contract that carried over into 2017. “I can proudly say that I had no part of the Trump-era stuff,” he said. “To me, that was not done for security. It was for racism.”

The Trump years were a profoundly affecting period for the Browns. Christie participated in a border wall lawsuit. Michael joined her at protests, though he had to keep a low profile because he was still working for the government. With Trump’s defeat, the couple believed the worst was behind them. Then Ducey’s project came along. Still, bad as it was, they expected that the conclusion of the midterms — with a Democrat winning the governor’s mansion — would spell the end of Ducey’s destruction of public lands. But then that didn’t happen either.

Michael used his experience managing government projects to catalogue the myriad ways in which Ducey ran roughshod over critical laws and regulations. He wrote to Arizona Sens. Mark Kelly and Kyrsten Sinema and Reps. Raul Grijalva and Ann Kirkpatrick, at the time all Democrats, to share his concerns. He did the same with the Arizona office of the International Boundary and Water Commission and the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality. He included photos. Nothing happened.

My efforts to obtain any sort of comment from the Forest Service on its lack of action were similarly fruitless. I called Silver to see if he was hearing any murmurs of activity from the feds. “It’s the same for us,” he told me. “It’s like, give me a fucking break. Your habitat is just getting trashed. If I did that, you’d have the cops arrest me, and yet you’re standing by.”

The veteran environmentalist continued to send Biden administration officials visual evidence from the field, including a post-midterms email with the subject line, “WHERE ARE YOU????????”

The impact of Ducey’s project was growing by the hour. By mid-November, all illusions that the feds would suddenly spring into action were gone. On the other side of the mountains, meanwhile, close encounters with the governor’s project were beginning to have a radicalizing effect. Kate Scott near the shipping container wall on the U.S.-Mexico border in the Coronado National Forest in Arizona, on Nov. 29, 2022.

North of Ducey’s container wall, a zigzagging road leads the way to Tucson. The views in Lyle Canyon are frequently stunning, but the backcountry highway is barely two lanes. The curves are blind. The shoulder is marked by dropoffs and walls of trees or earth. There are no lights.

Martin Brown — no relation to Michael and Christie — lives in the canyon and teaches high school art in Tucson. He treasures his scenic commute, but it requires taking off before dawn. The most dangerous portion of his drive is in the canyon. Last month, he nearly died there.

Brown had been passing the convoys of pickups that came racing down the canyon for weeks. “It’s like clockwork, every morning, around 6 a.m., I pass 10 to 12 of those monster trucks,” he told me. “These are not the shorties. These are the 40-footers,” Brown said. “When they come barreling around those sharp corners, they almost can’t avoid being in your lane.”

On November 15, Brown rounded a bend to find one of Ducey’s container-carting contractors fully in his lane and coming fast. The truck and trailer passed within inches. “I would say that was the closest I’ve come to death ever,” Brown said. “If I hadn’t been coffee’d up and alert that day, I wouldn’t have made it. It would have hit me head-on.”

Brown told his closest neighbor, Kate Scott, about his near-death experience. Scott, who had had her own close call with the governor’s contractors, was outraged. She’d had enough.

A veterinary technician by training, Scott runs the Madrean Archipelago Wildlife Center, where she rehabilitates injured raptors. She and her husband bought the secluded ranch where the center is located, 20 miles north of Mexico, in 1997. The couple has far more trouble with trespassing hunters than migrants. “I’m never scared,” Scott told me. “All that stuff that they’re always harping on on the news, it’s all baloney.”

Scott’s greatest worry is the environmental damage that the baloney is causing. In July 2020, she and a friend visited the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area, a world-famous birding destination where Trump was deploying explosives to make way for a 30-foot-tall bollard wall.

“I’ll never forget it,” Scott said. “When I saw it — it was like I was stabbed in the chest. It was a very visceral, very emotional feeling that I don’t think I’ve ever felt in my adult life.”

“It’s a crime against nature. Everyone in America should be mad because it’s going through their national forest.”

Scott organized protests and got to know other Arizonans fighting to protect their public lands. When she returned from a recent trip to find that those lands were once again under attack, she was horrified. “I felt the same way when I saw the Trump’s wall — that this cannot stand,” Scott said. “It’s a crime against nature. Everyone in America should be mad because it’s going through their national forest.”

“It’s another form of insurrection,” she argued. “You’re saying, ‘I’m not going to follow the rule of law, President Biden, I’m going to do what I want. This is my state.’”

Scott wasn’t the only one feeling that way. Jennifer Wrenn and her husband Andy Kayner live farther south down Lyle Canyon. They are among Arizona’s closest residents to Ducey’s wall. For more than a month, their mornings have begun with the clamoring of convoys passing their front door. They continue nonstop until sundown.

“Every day of the week. Sundays included,” Wrenn told me. “They’re very fast, very careless, and I’ve known several people who have been run off the road.”

Wrenn and Kayner reflect the wide blast radius of Ducey’s project: At the center are the containers, at the edges are Arizonans like them. Torn up by the governor’s convoys, the roads near the couple’s home have been nearly destroyed for a project ostensibly meant to keep them safe. They aren’t the only ones affected, Wrenn stressed: Access for boaters and anglers at popular Parker Canyon Lake, hunters in the national forest, and hikers of the famed Arizona Trail were all being impacted by Ducey’s project.

“It’s so unnecessary and wasteful. I mean, what could we do with $97 million?” Wrenn asked. “It’s a travesty and you’re reminded of it every five minutes — how stupid it is and how helpless we feel.”

Last month, Wrenn sent an email to her neighbors to see what could be done. She and Scott started talking. The Browns in Sierra Vista were looped in. Together, they began brainstorming the possibility of a protest at the construction site. Nobody knew what it would look like. Would the contractors run them off? Would they call the sheriff?

The group decided they needed to do a test run. On the morning of Sunday, November 20, Scott, Wrenn, and Kayner, along with Michael and Christie Brown, McSpadden, and a handful of others, drove out to the container wall. As usual, they were met by one of the site’s private security contractors. This time, however, they had numbers.

“We talk to the Border Patrol, the sheriff, the Forest Service,” the guard said. “They all have our back.” The locals pressed for names. The guard didn’t have any. “I’m out here trying to support my family,” he said. “That’s it.” When asked who he worked for, the man replied, “a security company.” He added that he previously served in the U.S. Marine Corps.

The residents stuck around as one hour bled into the next. They noticed the construction had stopped. At 3 p.m., the contractors packed up and left. They hadn’t put down a single container since the locals arrived. Jennifer Wrenn, 68, and Andrew Kayner, 71, outside their home near Elgin, Ariz., on Nov. 29, 2022.

On the morning of November 29, I climbed back into McSpadden’s truck. We followed Highway 83 south into Lyle Canyon. The test run at Coronado had been a revelation for the valley’s agitators: Not only was protest possible, but when people went to the site, the work also stopped.

Scott circulated a call to action to trusted contacts. “The rule of law must be followed and We the People will not be intimidated or dissuaded from enjoying our beautiful borderlands within the Coronado National Forest,” she wrote. “Make your Voice heard. Participate in the dialogue. Join us in this peaceful protest. Bring your signs, banners, songs and statements.”

Scott and the Browns had already arrived when McSpadden and I pulled up to a dirt intersection a short drive from the container wall. Wrenn and Kayner showed up soon after. They were joined by a handful of others. Everybody had their signs.

The sound of approaching trucks came echoing down the canyon. The protesters scrambled to their vehicles. At 10:30 a.m., they reached the ad hoc checkpoint that led to the wall. They didn’t stop. A private security contractor with a pistol on his belt held a walkie talkie to his ear as they passed. A voice crackled through the receiver: “They got all their vehicles coming in.”

The protesters arrived just as one of the massive military vehicles that ran containers to the end of the wall was preparing a delivery. McSpadden was standing on the Roosevelt Reservation with his camera as the vehicle approached. Protesters hurried to join him as the contractors climbed down from the truck and walked away. With the gargantuan container-mover half-parked on the border road, its one working headlight still on, Scott delivered an impassioned speech while the private security guards wandered over to the protesters’ cars and eyed their license plates.

Two hours after the protesters arrived, a black pickup with tinted windows pulled into the site. Two men stepped out. Badges swung from their necks as they approached. The larger of the pair was tall and burly, with khaki tactical pants, a fleece vest, and a flannel shirt. He introduced himself as Sgt. Tim Williams, head of the Cochise County Sheriff’s Department’s Southeastern Arizona Border Regional Enforcement task force. Better known as SABRE, it was the same unit that visited the Browns’s home a month before.

The unit was created in 2014, when Dannels took over as sheriff. Over the past decade, the Cochise County sheriff has made a name for himself describing chaos in his jurisdiction for Fox News viewers and Republican lawmakers. That message pays. In February alone, Dannels’s department received a promise of $14.9 million from Ducey’s border security fund. The first $2.7 million went to SABRE. Last month, Ducey approved an additional $5 million for a new “Border Operations Center” that would place regional law enforcement operations under Dannels’s command.

Williams explained that his office got a call about the protesters. “We just request that you guys keep it kind of civil and try not to get hurt,” he said. “You guys got any questions for us?”

“Well, actually I do,” said Michael Brown. “Do you know how many people actually cross from that mountain west?”

It was a question Williams clearly answered often. “Right around 1,000 a month that we know of, probably,” he said. “Between 500 and 1,000.”

Over the next hour, Williams painted a portrait of Coronado as a war zone. “Most of them are what we call military-aged males,” he said, invoking the language justifying lethal force that I often encountered covering U.S. drone strikes. “They’re between the ages of like 15 and 25, and they’re all coming across in large groups.”

Michael told the sergeant that he had cut wood in the area for more than a decade. “I’ve only seen one,” he said.

Williams countered that he had an archive of game cam footage proving that Cochise County was suffering from a historic wave of unauthorized border crossers, many of whom were dangerous criminals. I asked what the sergeant attributed this explosion to.

“The illegals will tell you directly that it’s President Biden has changed policy,” Williams said.

“Which policy?” I asked.

“The immigration,” he replied. “President Biden has made it easier for them to be here.”

When the topic turned to the container wall rising up before us, Williams suddenly became guarded. “Opinions are something I don’t talk about,” he said. “I know when you do any project like this, environmental studies have to be done and all that stuff.” I asked if he was aware those studies hadn’t been done here and that the governor was told that the project was unlawful.

“That I have no idea,” the sergeant said. “I know this is the Roosevelt easement. This is the federal government easement.”

The next morning, Coronado National Forest issued its first public statement on the ongoing destruction. The message: Stay away. “Last month, the State of Arizona initiated an unauthorized project to install numerous shipping containers in the Coronado National Forest which may be creating safety hazards,” the service said, citing the “unauthorized armed security personnel on-site.”

That afternoon, I spoke to Starr Farrell, the public affairs officer who circulated the alert. “We really don’t want a conflict,” she told me. Farrell acknowledged the damage Ducey’s “heavy machinery” had done to Forest Service roads and sounded genuinely alarmed when I told her that the governor’s private security contractors said her agency had their backs. “Oh,” she said. “Oh my.”

“This was an unauthorized placement of these shipping containers,” Farrell said. “That isn’t something we would ever encourage.” When I asked why the Forest Service wasn’t taking active steps to stop it, Farrell said it was out of her agency’s hands. The Department of Justice was calling the shots. “It’s been escalated up,” she said. “It’s outside of a normal conversation we could have on the ground here.”

For the protesters on the ground, the conflict that the Forest Service hoped to avoid had already begun. That same day, they were back at the governor’s renegade construction site. Once again, their presence stopped construction. It had become an ongoing effort to do what the federal government would not: protect public lands from illegal destruction.

“I thought they were going to kill some of these people out there.”

Over the next seven days, resistance to Ducey’s wall took a series of dramatic turns. Early on the morning of December 2, McSpadden returned to Coronado to find a new, younger group of demonstrators at the site. This time, instead of halting of construction, the governor’s contractors attempted to push forward with their work. McSpadden called from the scene. The connection was bad, but the words “really dangerous” came through.

Later that afternoon, he described a contractor navigating the arm of an excavator within a foot of protesters’ heads. “I thought they were going to kill some of these people out there,” he said. Then, out of nowhere, the work stopped, and the contractors again left. A place that had been so loud and chaotic for weeks was dead silent. “It was so stark,” McSpadden later told me. “It was like peace.”

Heavy rains that weekend brought construction to a halt. Ducey’s contractors had put down just 40 stacks of containers in five days, compared to the 20 to 30 they were averaging per day before. On December 5, a group of early risers shut construction by parking a car on the border road. Another day of work was lost. Ducey clearly needed to adjust.

The next morning, at 6:45 a.m., Scott returned to find the governor’s work crews had 17 dropped stacks of containers in the night. She alerted the growing group of volunteers. If Ducey’s contractors were going to work at night, then people needed to be on the ground at night. Within hours, a plan took shape. A shift schedule was created. Food and overnight supplies were purchased. Up in Lyle Canyon, Andy Kayner loaded his pop-up camper.

By nightfall, there were six people at the site. At 11 p.m., a line of headlights snaking down the canyon appeared in the distance. Two more protesters arrived. Together, the eight public land defenders needed to secure two locations: the staging area where Ducey’s containers were kept, and the end of the wall where the heavy equipment was parked. There was no tapping out. If they moved, construction would commence.

The contractors turned on their vehicles. Some slept while the activists stood. Four long, cold hours passed. At 3 a.m., the governor’s contractors gave up and left.

The sun rose the next morning on a movement that was gaining momentum. Word was spreading. Over in Santa Cruz County, to the west from Cochise, Sheriff David Hathaway had been monitoring Ducey’s efforts from the moment the shipping containers first appeared in Nogales. Hathaway was born in the border city, a fifth-generation Arizonan and a former Drug Enforcement Administration investigator and supervisor. His family has had ranch land in Cochise County, in precisely the area where Ducey was operating, for generations.

The sheriff hated everything about Ducey’s project. For one, it was plainly illegal, and the feds were doing nothing stop it. Hathaway, a Democrat, vowed to arrest Ducey’s contractors if their work crossed the county line — an unlikely scenario given that the governor’s project was slated to terminate just shy of his jurisdiction — and ordered his deputies to look out for contractors driving recklessly through Santa Cruz County communities. There was little more he could do. It was the feds’ responsibility to enforce federal laws, and despite the private messages Hathaway was receiving from Coronado law enforcement expressing their gratitude, they weren’t doing it.

After weeks of rising frustration, Hathaway wanted to thank the people who were finally doing what the feds would not. He climbed into his work truck and set off for Cochise County. Scott, Kayner, and Ethan Bonnin, a Center for Biological Diversity contractor, were at the site when the sheriff pulled in, alone and unannounced. Together, they told Hathaway about the standoff the night before. The sheriff was awestruck. Public land defenders Andy Kayner, Kate Scott, and Ethan Bonnin visit with Santa Cruz County Sheriff David Hathaway at an encampment blocking Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey’s illegal wall of shipping containers on Dec. 7, 2022.

When I later asked about his visit, Hathaway described how the governor’s justifications for the wall were as wrong as they were predictable. Lawmakers like Ducey, who made his millions selling ice cream, are often taken by harrowing “Sicario”-style accounts of border mayhem that they hear from men in uniform and disinclined to tell them no when they ask for more money and resources, he argued.

“Of course, they’re going to say that. It would be like going to Raytheon and asking them, ‘Should we have another war in the Middle East?’”

“Of course, they’re going to say that,” Hathaway said. “It would be like going to Raytheon and asking them, ‘Should we have another war in the Middle East?’” Peddling border fear sells among some Arizona voters, the sheriff said, particularly retirees from out of state who rarely venture further south than Phoenix. It was no coincidence that the governor’s project began and ended in Cochise County, he argued. “Sheriff Dannels is in lockstep with Ducey. He’s not going to oppose anything that Ducey does,” Hathaway said. It had nothing to do with safety: “It’s just political rhetoric.” The two men were appealing to the same crowd.

“I’ve been going out there since I was a baby,” the sheriff said. “It’s very safe.”

Scott was still buzzing from Hathaway’s visit when I pulled into the new encampment at the foot of the container wall and unloaded my tent. “It was like he didn’t want to leave,” she told me. “He’s really, really appreciative.”

The sun was disappearing, and the temperature was dropping. Kayner’s camper was parked at the end of the wall with the contractors’ equipment. A security guard was posted nearby in a pickup. Sitting inside his vehicle, Kayner was steeling himself for whatever came next. “It’s going to be more painful now because we got to be here at night, but it’s certainly doable,” he told me. For the retired engineer, stopping Ducey’s project was about pulling Arizona back from a dangerous brink.

“This kind of thing happened with the Malheur Bird Refuge,” Kayner said. He wasn’t the first one to reference the 2016 anti-government takeover of public land in Oregon. “They just stayed there, and authorities didn’t go in and chase them out and put an end to it,” he said. That inaction, Kayner argued, “empowers this kind of thinking that we can overpower the federal government, the people of the United States, and do what we want to do.”

“That’s what this wall is out here,” he said. “It’s one man going against the law.”

No one knew if the contractors would try another night installation, but they were ready if they did. Instead, strangers and neighbors shared soup under the stars. At one point, Scott described how a wave of energy had rushed over her at dusk. Maybe it was just the hawk she had seen hovering over the now quiet work site, but it felt like it was something more. “I don’t know,” she said, “I just think that we won.” The next morning, we awoke to frost on our tents. The desert was still. The governor’s men did not return for work. They have not put down a container since.