On the morning of September 21, 1976, Orlando Letelier, the former foreign minister of Chile living in exile in the United States, was driving to work in downtown Washington, D.C., when a bomb planted in his car exploded, killing him and one passenger while wounding another.

Letelier was assassinated in the heart of Washington by the brutal regime of Chilean President Augusto Pinochet, a far-right dictator who gained power in a 1973 coup backed by the Nixon administration and the CIA, overthrowing the socialist government of President Salvador Allende. Letelier served as foreign minister for Allende, and later was arrested and tortured by Pinochet. After a year in prison, Letelier was released thanks to international diplomatic pressure and eventually settled in Washington, where he was a prominent opponent of the Pinochet regime.

Even in exile, Letelier still had a target on his back. The Pinochet regime, along with the right-wing governments of Argentina and Uruguay, launched a vicious international assassination program — code-named Operation Condor — to kill dissidents living abroad, and Letelier was one of Operation Condor’s most prominent victims.

Nearly 50 years later, the full story of Letelier’s assassination, one of the most brazen acts of state-sponsored terrorism ever conducted on American soil, is still coming into focus.

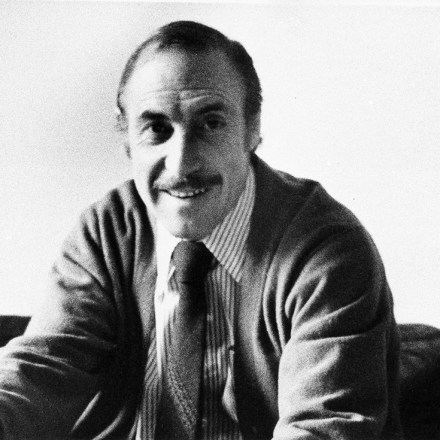

Now, the 100th birthday of former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, which has been marked in the press by both powerful investigations as well as puff pieces and hagiography, offers an opportunity to reexamine the Letelier assassination and the broader U.S. role in overthrowing Chile’s democratically elected government in order to impose a brutal dictatorship. It was one of the darkest chapters in Kissinger’s career and one of the most blatant abuses of power in the CIA’s long and ugly history.

Making a Coup

The first steps in the covert campaign by President Richard Nixon, Kissinger, and the CIA to stage a coup in Chile began even before Allende took office. Their actions were eerily similar to President Donald Trump’s coup attempt following his defeat in the 2020 presidential election, when Trump tried to block the congressional certification of the election, culminating in the January 6, 2021, insurrection.

On September 4, 1970, Allende came in first in the Chilean presidential election, but since he did not gain an outright majority, Chile’s legislature had to choose the winner. Scheduled for late October, that legislative action was supposed to be a pro-forma certification of Allende, the first-place candidate, but Nixon, fueled by anti-communist paranoia that led him to oppose leftist governments all around the world, wanted to use that time to stop Allende from coming to power.

The Nixon administration pursued a two-track strategy. The first track included a campaign of propaganda and disinformation against Allende, as well as bribes to key players on Chile’s political scene and boycotts and economic pressure from American multinational corporations with operations in Chile.

The second track, which was far more secretive, called for a CIA-backed military coup.

On September 15, 1970, in a White House meeting, Nixon ordered CIA Director Richard Helms to secretly foment a military coup to stop Allende from becoming Chile’s president. Also attending the meeting was Kissinger, who was then Nixon’s national security adviser, and Attorney General John Mitchell. Helms later said that “if I ever carried a marshal’s baton in my knapsack out of the Oval Office, it was that day.”

Helms and the other CIA officials involved didn’t think they had much of a chance of mounting a successful coup — and they were right, at least in 1970. Their coup efforts failed that year, but a renewed coup attempt succeeded in 1973, during which Allende died and Pinochet came to power.

Pinochet’s Guardian

By 1976, three years after gaining power in the CIA-backed coup, Pinochet had created a bloody police state, torturing, imprisoning, and killing thousands. Despite its draconian practices, Pinochet’s intelligence service enjoyed close relations with the CIA, while Kissinger remained Pinochet’s guardian in Washington, fending off congressional efforts to punish Pinochet’s regime over its human rights record.

Kissinger held a secret meeting with Pinochet to privately tell the dictator that he could ignore the public upbraiding that he was about to give him.

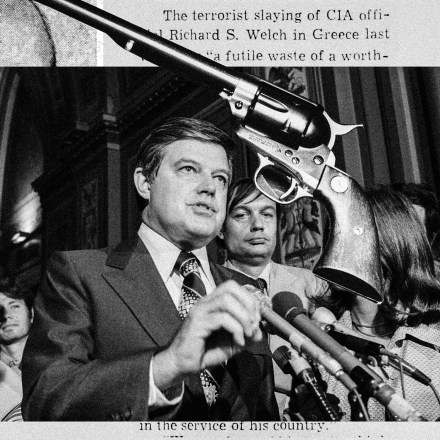

By September 1976, when Letelier was killed, Pinochet had good reason to believe he could get away with murder in the heart of Washington. In fact, Letelier’s assassination may have been enabled by a secret meeting between Pinochet and Kissinger three months earlier.

On June 8, 1976, Kissinger — by then the secretary of state for President Gerald Ford — met with Pinochet at the presidential palace in Santiago, just as Pinochet’s vicious human rights record was becoming a major international issue. The Church Committee, the Senate’s first investigation of the CIA and the rest of the U.S. intelligence community, had just completed an inquiry into the CIA’s efforts to foment a coup in Chile, and had closely examined a CIA scheme in 1970 to kidnap a top Chilean general who had refused to go along with the CIA-backed anti-Allende plots. As part of its CIA-Chile investigation, the Church Committee secretly interviewed the exiled Letelier.

In the summer of 1975, Church Committee staffer Rick Inderfurth and another staffer quietly interviewed Letelier at his home in Bethesda, Maryland, where he was living with his wife and four children. Inderfurth questioned Letelier about a wide range of issues, including how the overt and covert policies of the CIA and the Nixon administration in the years leading up to the 1973 coup had destabilized the Allende government. Letelier provided valuable insights for the Church Committee’s investigation, but he did not testify in public during its hearings on Chile. The fact that Letelier was interviewed by the Church Committee was reported for the first time in my new book, “The Last Honest Man.”

Even though he lived in Washington, Letelier wasn’t safe from Pinochet.

After the Church Committee’s investigation and other disclosures, Congress was seeking to punish Pinochet’s regime for its use of torture and other human rights abuses, and Letelier met with congressional leaders about how to hold Pinochet accountable. Kissinger, who held broad sway on foreign policy under Ford, was under mounting pressure to publicly reprimand Pinochet.

Kissinger agreed to travel to Chile in June 1976 to give a speech to publicly criticize Pinochet on human rights. But just before his address, Kissinger held a secret meeting with Pinochet to privately tell the dictator that he could ignore the public upbraiding that he was about to give him. Kissinger made it clear to Pinochet that his public criticism was all for show and part of an effort to placate the U.S. Congress. During their private talk, Kissinger made clear that he thought the complaints about Pinochet’s human rights record were just part of a left-wing campaign against his government. Kissinger emphasized that he and the Ford administration were firmly on Pinochet’s side.

“In the United States, as you know, we are sympathetic with what you are trying to do here,” Kissinger told Pinochet, according to a declassified State Department memo recounting the conversation, published in “The Pinochet File,” by Peter Kornbluh. “I think that the previous government [Allende’s administration] was headed toward Communism. We wish your government well. … As you know, Congress is now debating further restraints on aid to Chile. We are opposed. … I’m going to speak about human rights this afternoon in the General Assembly. I delayed my statement until I could talk to you. I wanted you to understand my position.”

After getting Kissinger’s reassurances, Pinochet began to complain that the U.S. Congress was listening to his enemies — including Letelier.

“We are constantly being attacked” by political opponents in Washington, Pinochet told Kissinger. “They have a strong voice in Washington. Not the people in the Pentagon, but they do get through to Congress. Gabriel Valdez [a longtime Pinochet foe] has access. Also Letelier.” Pinochet bitterly added that “Letelier has access to the Congress. We know they are giving false information. … We are worried about our image.” It is not known whether Pinochet was aware that Letelier had been a secret witness for the Church Committee, or whether the dictator only knew about Letelier’s more public lobbying efforts to get Congress to take action against the Pinochet regime.

During the June 8 meeting, Kissinger did not respond to Pinochet’s complaints about Letelier. Instead, he told Pinochet, “We welcomed the overthrow of the Communist-inclined [Allende] government here. We are not out to weaken your position.” Given the context of the meeting, during which Kissinger signaled to Pinochet that the Ford administration was not going to penalize him for his regime’s human rights record, Kissinger’s silence in the face of Pinochet’s complaints about Letelier must have been viewed by Pinochet as a green light to take brutal action against the dissident.

Kissinger took further action later in the year that gave Pinochet the freedom he needed to move against Letelier. After the U.S. found out about Operation Condor, State Department officials wanted to notify the Pinochet regime and the governments of Argentina and Uruguay not to conduct assassinations. But on September 16, 1976, Kissinger blocked the State Department’s plans. Kissinger ordered that “no further action be taken on this matter” by the State Department, effectively blocking any effort to curb Pinochet’s bloody plans. Letelier was assassinated in Washington five days later.

Letelier was one of three witnesses of the Church Committee who were murdered, either before or after they talked to the committee. (The other two were Chicago mobster Sam Giancana and Las Vegas gangster Johnny Roselli, who were both involved in the CIA’s secret alliance with the Mafia in the early 1960s to try to kill Fidel Castro, a scheme that was the subject of a major investigation by the Church Committee.) Meanwhile, Pinochet remained president of Chile until 1990.

Pinochet was arrested in London in 1998 in connection with the human rights abuses he committed while in power, and was placed under house arrest in the United Kingdom until 2000, when he was released on medical grounds without facing trial in Britain. He returned to Chile and faced a complex series of investigations and indictments — but no actual trial in his homeland — until his death in 2006.

Henry Kissinger has never been held to account.