Since 2015, Rep. Betty McCollum, D-Minn., has been the leading congressional critic of Israel’s military detention of Palestinian children, introducing multiple pieces of legislation that would bar Israel from using U.S. military aid to arrest Palestinian youth.

By targeting Israel’s detention of Palestinian children — just one aspect of Israel’s military occupation, but one that involved a highly vulnerable population — McCollum was attempting to make her bills appeal to the widest swath of Democrats possible. For most others in her party, the check the U.S. wrote to Israel every year was not up for debate.

McCollum is now planning to introduce legislation on Thursday that would bar U.S. aid from subsidizing a wider array of Israeli occupation tactics, an indication of just how far the debate over U.S. aid to Israel has come in the past six years.

“There is nothing out of the ordinary about conditioning aid. … All taxpayer funds provided by Congress to foreign governments in the form of aid are subject to conditions in a myriad of generally applicable laws, yet the $3.8 billion provided to Israel by the State Department has no country-specific conditions despite Israel’s systemic violations of Palestinian human rights,” McCollum told The Intercept. “I don’t want $1 of U.S. aid to Israel paying for the military detention and abuse of Palestinian children, the demolition of Palestinian homes, or the annexation of Palestinian land.”

McCollum’s bill is the result of years of work by Palestinian rights activists to cut or condition aid to Israel. These calls have been fueled by reports of U.S.-made weapons being used to kill Palestinian civilians, whether with Hellfire missiles fired by Israeli fighter jets on homes in Gaza or with U.S.-made rifles used to gun down Palestinian protesters. Human rights organizations have documented the Israeli military’s repeated use of bulldozers produced by the Illinois-based Caterpillar company to demolish Palestinian homes.

“I don’t want $1 of U.S. aid to Israel paying for the military detention and abuse of Palestinian children, the demolition of Palestinian homes, or the annexation of Palestinian land.”

The legislation has been endorsed by more than 20 groups, including mainstays in the Palestinian rights movement like the Adalah Justice Project and Jewish Voice for Peace Action, as well as the liberal pro-Israel group Americans for Peace Now and the progressive Justice Democrats, which focuses on launching primaries against establishment Democrats.

Fifty-three percent of Democratic voters told Gallup this year that they support increasing pressure on Israel — an increase of 10 points since 2018 — yet most Democrats in the House and Senate do not support conditioning aid, and the bill faces steep odds of even getting a hearing in the House Foreign Affairs and Appropriations committees. Still, it’s the most significant effort yet by progressive Democrats to broach what was once an unthinkable red line: changing the nature of U.S. military aid to Israel so that U.S. aid is banned from furthering Israeli human rights abuses. It’s a remarkable development in an institution long thought to be a permanent stronghold for the pro-Israel lobby.

“The movement in Congress is unprecedented,” said Raed Jarrar, a Palestinian American analyst and the former advocacy director for American Muslims for Palestine. “I never dreamed that we would have bills banning the U.S. government from funding Israeli activities that are in violation of U.S. law or international law.”

Broader political dynamics — the combination of Israel’s hard-right direction, its apartheid system in the occupied territories, and Barack Obama’s clashes with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu followed by the Trump-Netanyahu alliance — have created space for this discussion to come to the fore.

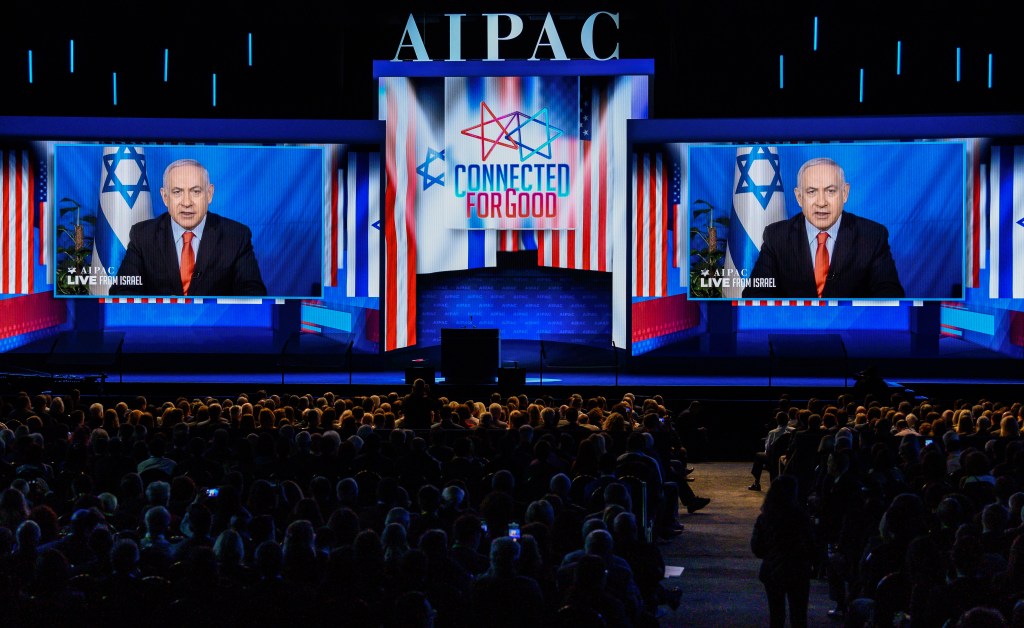

Benjamin Netanyahu, prime minister of Israel, speaks via video to the American Israel Public Affairs Committee during the Policy Conference in Washington, D.C., on March 26, 2019.

These developments have also pushed groups closer to the Democratic mainstream to advocate for restrictions on how U.S. aid can be used by Israel. J Street, a liberal group that supports U.S. aid to Israel but opposes Israel’s military occupation, is backing McCollum’s bill — the first time the group backs one of her efforts to ensure that U.S. military aid to Israel comes with strings attached.

In addition to encouraging congressional support for McCollum’s bill, the group, whose annual conference will begin on April 18, will lobby members of Congress to introduce language to the foreign appropriations bill to restrict U.S. military aid from furthering policies of annexation or the exercise of permanent military control over a territory under occupation. While J Street’s language does not single out Israel, the group sees it as prohibiting U.S. aid from supporting those Israeli actions.

The lobbying marks a significant shift for a group seen as the most influential liberal Jewish group working on Israel in Washington. J Street’s endorsement or opposition to legislation around Israel carries significant weight in the Democratic caucus, and Palestinian rights advocates — and even some within J Street — have often criticized the group for standing in the way of legislative efforts to condition U.S. aid to Israel.

“We believe that every dollar of our current security assistance to Israel should go towards measures that address Israel’s actual security needs — and that none of that money or the equipment bought with it should be used in connection with the demolition of Palestinian communities, settlement expansion or other actions that facilitate de facto annexation in the occupied West Bank,” said Dylan Williams, J Street’s senior vice president of policy and strategy who leads the government affairs team. “Policies like that trample on Palestinian rights and undermine Israel’s own long-term future as a democratic homeland for the Jewish people.”

J Street’s position is in stark contrast to that of other pro-Israel groups. In March, as part of its virtual national council meeting, the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, or AIPAC, lobbied members of Congress to sign on to a letter authored by Reps. Mike McCaul, R-Texas, and Ted Deutch, D-Fla., that criticizes efforts to condition aid to Israel.

“The Democratic Party has been clear in its opposition to putting additional conditions on military assistance to Israel. … While there are a few Democrats who want additional conditions, the party has spoken clearly and unambiguously against such efforts,” said Rachel Rosen, spokesperson for the lobby group Democratic Majority for Israel, which has spent heavily against lawmakers and candidates who have been critical of Israel.

President Joe Biden has taken some steps to reverse the Trump administration’s unprecedented practice of gifting the Israeli government whatever they wanted, including by reversing Donald Trump’s decision to cut off all humanitarian aid to Palestinians. But the Biden administration has also made clear that it will not fundamentally change the U.S.-Israel relationship. Biden called the idea of conditioning aid to Israel “bizarre” during the 2020 campaign and has stocked his administration with pro-Israel officials who have ruled out pressuring the country over its treatment of Palestinians.

The task for the Palestinian rights movement, then, is to find a way to convince the majority of Democrats to join their side, or to successfully unseat enough lawmakers whose support for Israel is unconditional and immovable, such that the rest of the caucus recognizes where the political winds are shifting. This has begun already, perhaps most notably with the ouster of longtime congressman and House Foreign Affairs Committee Chair Eliot Engel by Jamaal Bowman last year. It’s a monumental mission that will likely take years to reach.

While conditioning military aid would mark a historic rupture in the U.S.-Israel relationship, sending a message to Israel that the days of committing human rights abuses with blank American checks are over, it would also be a return to what was the norm in Washington just a few decades ago.

U.S. military assistance to Israel dates back to 1962, when President John F. Kennedy decided to sell Israel anti-aircraft missiles. Since then, the U.S. has given the Jewish state over $110 billion in military funding, making it the largest recipient of U.S. foreign aid in history.

This military assistance falls under the rubric of the Foreign Assistance Act, which stipulates that U.S. aid cannot be used by foreign countries to commit human rights violations, and the Arms Export Control Act, which limits foreign military forces from using such aid for purposes beyond “self-defense.”

Beginning with Gerald Ford’s presidency, successive U.S. presidents used military aid as a tool to pressure Israel to make concessions to its neighbors, acting on a belief that Israeli-Arab peace was crucial to tamping down tensions in a resource-rich region that had become a venue for U.S.-Soviet proxy battles. The regional conflict had begun with Israel’s declaration of statehood in 1948, which prompted surrounding Arab states to invade, ostensibly to defend Palestinians, although Arab countries had their own territorial designs on Palestine. The conflict intensified with Israel’s lightning defeat of Arab nations in the 1967 war, which saw Israel capture and occupy the Syrian Golan Heights, the Egyptian Sinai Peninsula, and the Palestinian West Bank, Gaza Strip, and East Jerusalem.

In 1975, the Ford White House temporarily suspended delivery of fighter jets to Israel in a bid to get Israel to agree to partial withdrawal from Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula. In September of that year, Israel relented, carrying out a partial withdrawal. In 1977, Jimmy Carter threatened to withhold aid to Israel if it didn’t come to an agreement with Egypt over full withdrawal from the Sinai, which Israel eventually did after signing the Camp David Peace Accords with Egypt. In April 1983, Ronald Reagan held up the delivery of F-16 fighter jets because of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, authorizing the shipment only after Israel agreed to withdraw its forces. And in 1991, George H.W. Bush blocked $10 billion in U.S. loan guarantees to Israel and demanded that Israel stopped building illegal settlements in the West Bank and Gaza; the loans started flowing only after Israel agreed to participate in the Madrid Peace Conference, alongside Palestinian, Jordanian, Syrian, and Lebanese officials, as well as limits on settlement construction.

Bush, however, was the last president to use U.S. aid to compel Israel to act a certain way.

“For most places in the pro-Israel community … there doesn’t seem to be a very significant appetite for putting pressure on Israel.”

According to Dan Kurtzer, former U.S. ambassador to Israel from 2001 to 2005, this shift was the result of a decline in hands-on foreign affairs experience among U.S. presidents, combined with the fact that “pro-Israel, both Jewish and, particularly, evangelical Christian communities, have grown into very outsized political roles. They’re not just in politics in our country, but also in the funding of the politics. And for most places in the pro-Israel community, whether from the right or left, stopping short of the progressive wing on the left, there doesn’t seem to be a very significant appetite for putting pressure on Israel.”

Among the key actors were AIPAC, which had established itself as a singularly influential force by the 1990s, and Christians United for Israel, a group of mostly white, Christian, evangelical Republicans whose influence grew after the September 11 attacks. Both AIPAC and CUFI mobilized millions of people and poured millions more into campaign coffers in pursuit of their interests.

In the early 2000s, when Israel ramped up military operations against Palestinians during the Second Intifada, killing civilians, some U.S. officials questioned whether Israel was using U.S. equipment legally and thought the U.S. ought to send a warning to Israel, according to Lawrence Wilkerson, who served in the State Department’s Policy Planning Staff from 2001 to 2002.

“We knew it would never get past the secretary,” said Wilkerson, referring to then-Secretary of State Colin Powell. “It would never get sent. The White House would not permit it.”

Instead, successive White Houses agreed to provide even more U.S. aid to Israel, without any specific conditions on how that aid can be used — even during periods of tension between the two countries.

Obama’s relationship with Netanyahu was famously cold, clashing over Israel’s settlement expansion in the West Bank, which in turn imperiled the prospects for a Palestinian state, and over Netanyahu’s meddling in U.S. politics to torpedo the Iran nuclear deal. Nevertheless, in 2016, Obama and Netanyahu struck a record-setting Memorandum of Understanding, in which the U.S. promised to give Israel $38 billion in military aid between 2019 and 2028.

When the Obama administration “negotiated the memorandum of understanding, they wouldn’t consider using those talks as leverage to get Israel to stop problematic activity, including settlement expansion. They siloed security assistance and had those discussions separately,” said Zaha Hassan, a Palestinian human rights lawyer and visiting fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “This is Biden’s position as well — that security assistance benefits the U.S., so we don’t want to condition that.”

Raising questions about U.S. military aid to Israel was “third-rail politics” in D.C. for many years, Jarrar, the Palestinian American analyst, said. “If you touch it, you’ll get electrocuted.”

Just over a decade ago, the prevailing assumption among Palestinian rights advocates was that appealing to U.S. audiences, let alone politicians, to question U.S. weapons sales to Israel was futile, according to Brad Parker, who began to volunteer with the Ramallah-based Defense for Children International – Palestine, or DCIP, in 2009.

That same year, though, an intense Israeli assault on the Gaza Strip, the Palestinian coastal area under Israeli blockade since 2007, began to change the conversation. Dubbed Operation Cast Lead, Israel’s U.S.-backed attack killed 1,400 Palestinians, the vast majority of them civilians. Amnesty International called the assault “22 days of death and destruction.” On college campuses, student activism for Palestinian rights, led by Students for Justice in Palestine chapters, surged. Over the next five years, 24 SJP chapters presented resolutions before student governments to end their university’s investments in companies that profited off of Israeli abuses. Eleven of them passed — eight more than the total passed between 2005 and 2008.

The changing American landscape got Parker’s attention, and at the end of 2014, Parker, who had joined DCI’s staff as an international advocacy officer, pitched them an idea for a D.C.-based legislative campaign centering on Palestinian children called “No Way to Treat a Child.” The group agreed, and in early 2015, along with the American Friends Service Committee’s Jennifer Bing, DCIP approached McCollum about doing something regarding the Israeli army’s practice of arresting, detaining, and abusing Palestinian children throughout the occupied West Bank. In addition to her reputation as an advocate for children’s rights, McCollum had also previously voted against AIPAC-backed legislation that humanitarian organizations warned would make it difficult to provide health care for Palestinians. After McCollum voted against the bill, she said an AIPAC member in her district had called her a terrorist supporter, and McCollum, in a public letter, demanded an apology. (AIPAC denied this account.)

In June 2015, McCollum authored a letter, co-signed by 17 other members of Congress, calling on then-Secretary of State John Kerry to raise Israel’s abuse of Palestinian children in his discussions with Israeli officials. Since then, McCollum has authored two bills that would prohibit U.S. military aid from being used by Israel to detain Palestinian children — though it has been a somewhat lonely journey.

“In the last Congress, fewer than 30 Democrats supported my legislation to prohibit Israel from using the U.S. military aid they receive to mistreat or torture Palestinian children,” McCollum told The Intercept. “Until the lives and futures of millions of Palestinians are made a priority by Congress, nothing will change. But I am determined to keep trying and I hope more of my colleagues will join me in working for peace, justice, and human rights for Palestinians and Israelis alike.”

“Why is de jure annexation more problematic than actual on-the-ground activities that lead to home demolitions, residency revocation, exploitation of Palestinian resources?”

Last year, as Netanyahu considered officially annexing large swaths of the West Bank to Israel with Trump’s support, critics of Israel were galvanized. McCollum introduced a House bill that would prohibit U.S. aid to Israel from being used in territory annexed by the state. In the Senate, Chris Van Hollen, D-Md., led the introduction of an amendment to the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act that would prohibit Israel from using U.S. aid in carrying out annexation of the occupied West Bank. The amendment did not get a vote in the Republican-controlled Senate, but it marked the first time U.S. senators raised the idea of legislating restrictions on U.S. aid to Israel.

Ultimately, Netanyahu backed down on his annexation plan in exchange for the United Arab Emirates normalizing diplomatic relations (though human rights groups say Israel’s de facto annexation of Palestinian land continues apace). When that happened, the energy behind placing restrictions on U.S. aid dissipated, at least in the Senate.

“When it came down to de jure annexation they were willing to talk about conditionality and settlements, but only in the context of Israel taking this official step,” said Hassan, the Palestinian human rights lawyer. “Why is de jure annexation more problematic than actual on-the-ground activities that lead to home demolitions, residency revocation, exploitation of Palestinian resources?”

Over the last couple of years, a small group of progressive Democrats in Congress has been trying to forge a new reality on U.S policy toward Israel. It includes Reps. McCollum, Rashida Tlaib, Ilhan Omar, Mark Pocan, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, as well as Sen. Bernie Sanders. The group also includes Reps. Marie Newman and Jamaal Bowman, whose primary challenges to pro-Israel hawks last year signal that being a sharp critic of U.S. support for Israel no longer means destroying one’s electoral chances.

Bowman, who backed conditioning aid to Israel, unseated Eliot Engel, an entrenched and powerful incumbent from New York, while Newman, an anti-bullying activist, took on staunch AIPAC ally Dan Lipinski in Illinois.

In a position paper published by her campaign in 2019, Newman said she’s against U.S. military aid being used by Israel to maintain its military occupation of Palestinian land and that she supports legislation to bar U.S. aid from subsidizing Israel’s detention of Palestinian children.

That posture stood in sharp contrast to Lipinski, who had co-authored the Protect Academic Freedom Act in 2014, which would bar federal funds to universities if any organization funded by the school supports the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement, or BDS, targeting Israel over its human rights abuses.

During the 2020 Democratic primary, Israel advocacy groups contributed about $75,000 to Lipinski, who attacked Newman as “anti-Israel” and likened her to Omar, whose 2019 comments denigrating the pro-Israel lobby unleashed a wave of attacks on her. In the Bowman-Engel race, Democratic Majority for Israel spent about $2 million in TV ads and mailers in support of Engel, while Pro-Israel America PAC and NorPac, two Israel advocacy groups that focus on electoral campaigns, gave Engel over $260,000 in contributions.

“When progressives do take critical stances towards the occupation, there is definitely a price to pay for that.”

“When progressives do take critical stances towards the occupation, there is definitely a price to pay for that because of the work of DMFI, AIPAC and other affiliated foreign policy hawks, who will spend hundreds of thousands of dollars, or sometimes millions of dollars, to destroy a progressive challenger,” said Waleed Shahid, spokesperson for Justice Democrats, which had backed both Bowman’s and Newman’s campaigns.

Newman’s race against Lipinski was largely fought around his opposition to abortion rights, a position out of step with most Democratic primary voters. Still, Newman’s outspokenness on Palestine boosted her in an ethnically mixed district that includes about 110,000 Arab Americans, the majority of them Palestinian. Lipinski’s anti-BDS bill and alliance with AIPAC angered many Palestinians in the district. Combined with an energetic Democratic primary base looking to punish one of the most conservative Democrats in the House, it was enough to put Newman over the top.

Democrat Marie Newman campaigns in the Archer Heights neighborhood of Chicago on March 9, 2020.

This year, Newman was the first member of Congress to criticize Israel for not extending its Covid-19 vaccination program to Palestinians living under Israeli military occupation. And in March, she was one of 10 progressive Democrats to sign Tlaib’s and Pocan’s letter to Secretary of State Antony Blinken, calling on him to investigate whether Israel unlawfully used U.S.-made military equipment to demolish Palestinian homes.

“You can’t violate international law. You can’t use aid that we’re giving you to hurt other folks that live with you, or side by side with you. These are just golden rules, right?” Newman told The Intercept. “It was perfectly logical from a humanitarian rights standpoint to make sure that we continue to be consistent with every country, and right now we’re not being consistent with Israel.”

Beth Miller, Jewish Voice for Peace Action’s government affairs manager, noted that the sea change in congressional discourse is due to new members of Congress who are aligning their domestic progressive agenda with foreign policy issues like conditioning military aid to Israel and ending U.S. support for the Saudi war in Yemen.

Still, Miller noted, these advocates face another steep challenge: Biden’s firm commitment to the status quo of unconditional U.S. aid for Israel.

“What that means is that we just need to push harder for that fight to happen in Congress, because there is a robust debate happening in the House, and there’s room for a much more robust debate to happen in the Senate,” Miller said. “We’re going to be pushing for as many different versions of vehicles that condition or cut military funding as we can get, and vehicles that center Palestinians and the impact of Israeli government policies on Palestinians, and force Democrats to go on the record time and time and time again saying whether or not they support our tax dollars being used to oppress Palestinians.”

Mairav Zonszein contributed reporting to this story.