DEKALB COUNTY, Ga. — Dozens of protesters began gathering early Monday morning in a small, unremarkable park in southeast Atlanta. By 9 a.m., over 400 people — a coalition of local Atlantans and visiting activists from around the country — had assembled to attend a day of protests dubbed “Block Cop City.” The event was just the latest mass demonstration in over two years of resistance against the construction of a vast police training facility, known as Cop City, over hundreds of acres of Atlanta’s forest land.

Cops reacted to the day of action by attacking a slow-moving, peaceful march with tear gas and rubber bullets, just the latest reminder of why the compound, designed to further militarized counterinsurgency policing, should never be built.

Organizers were clear from the start: The protest activities — as had been agreed on in hourslong meetings in the prior days — would not involve property damage to construction vehicles at the site of the planned police facility. The tactic had been tried before, when a small amount of vandalism during a March day of action led to indiscriminate arrests and overreaching state domestic terrorism charges against 42 activists.

Monday’s participants planned simply to march, carrying banners and giant handmade puppets, to the Cop City construction area in the Weelaunee Forest, where they would plant nearly 100 saplings on cleared forest land.

Soon after the march turned onto a road with almost no traffic on it, lines of cops in riot gear amassed to block demonstrators’ route to the forest. Dozens of police vehicles swarmed the area, including an armored urban tank dubbed “the Beast.” As the marchers pushed slowly forward, the police moved in with shields and batons, shooting rubber bullets and launching flash-bang grenades and tear-gas canisters at the tightly packed group. Clouds of tear gas rolled over dozens of nearby, clearly identified journalists, myself included.

The protesters stayed in formation; they turned and marched back to their starting point, with a handful of activists hurriedly planting the tree saplings along the roadside.

“Ready to Plant Trees”

Now deep into its second year of organized, multifaceted resistance, the movement to stop Cop City and defend the Atlanta forest has again and again brought to glaring light the old lie: that police can be trusted to respect civil rights.

“Despite numerous stated commitments from religious leaders and city officials to honor the right to protest, armed riot police terrorized the crowd with tear gas grenades, attack dogs, clubs and ballistic shields,” said the Block Cop City organizers in a statement following the march.

The Cop City project was, of course, not blocked on Monday, but the abolitionist, environmentalist movement once again proved its staying power against aggressive police repression. Since its inception, activists opposing the $90 million police training facility have been attacked by police, mass arrested, and, in the intolerable case of Manuel “Tortuguita” Terán, riddled with 57 police bullets and killed.

Protesters face felonies for handing out flyers and fundraising for camping supplies. The government explicitly deemed opposition to Cop City a criminal enterprise when, in September, it announced racketeering charges against 61 activists, most of whom already face state domestic terror charges, for typical social justice activities like information sharing and mutual aid organizing. One such defendant, Indigenous activist Victor Puertas, was handed over to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and remains in detention facing deportation in addition to the egregious criminal charges.

“Now planting shovels are weapons. What’s next? Midnight raids for owners of muck boots?”

Meanwhile, an activist effort to get a public vote on Cop City on the recent November ballot had garnered sufficient signatures from the public — over 100,000 of them — but was obstructed by the city government in a blatant assault on democratic processes.

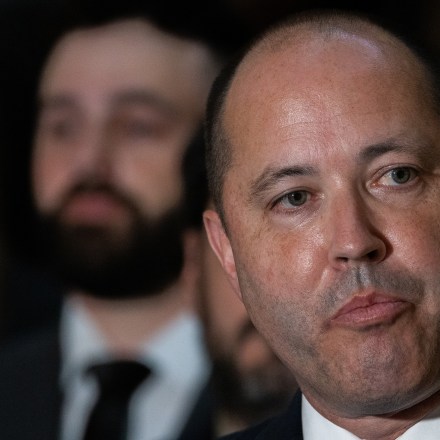

Following Monday’s demonstration, Atlanta Police Chief Darin Schierbaum held a press briefing to defend the cops’ use of tear gas and other weapons. He claimed the protesters were “prepared to do harm” and pointed to a line of gardening tools — dibbles specifically — police had taken from the march site. These were, of course, the tools activists were using to plant saplings.

“People were really ready to plant trees,” said an organizer who helped bring 75 oak seedlings, 25 pines, and elderberry cuttings to the event. (She asked to remain anonymous for fear of police harassment.) “First it was terrorism if you had muddy clothes,” Sam, a Texas-based organizer with the Austin Weelaunee Defense Society who asked for anonymity, told me. Police had used mud on the shoes of activists, in a forest, to justify the March arrests for domestic terrorism. “Now planting shovels are weapons. What’s next? Midnight raids for owners of muck boots?”

“People Are Determined”

Despite the blunt, repressive instruments deployed by police, those fighting to defend the forest have never stopped. Instead, they adapted and shifted tactics. None of the activists I spoke to on Monday, many with skin and eyes still burning from tear gas, felt the march was a failure. They are already planning for their next steps.

A campaign, Uncover Cop City, is underway to put public pressure on insurance companies Nationwide and Accident Fund to end their subsidiaries’ liability contracts with the Atlanta Police Foundation, the corporate-backed nonprofit behind Cop City. Without the insurance contracts, Cop City’s construction is dead in the water. Previous direct targeting of companies involved in the project have led several contractors to drop out.

“People are determined to see this struggle through to the end,” May Johnson, a resident of the neighborhood next to the forest imperiled by Cop City who has been active in the movement since its beginning, told me. “The movement is quick to adapt its strategies and persist despite repression.”

The fight to defend the forest matters on its own terms for those living nearby. The forest’s destruction, air and noise pollution, flooding risks, and the considerable increase in police presence it will bring is a threat to the adjacent majority Black and low-income neighborhood. The cab driver who drove me to the protest staging ground, a Black lifelong Atlanta resident, was unequivocal. “Nobody wants that thing built,” he said. My Airbnb host opposes Cop City; his father grew up in the neighborhood on the forest’s edge.

The widespread opposition is how a small group of activists, in a matter of weeks, collected 100,000-plus signatures from locals who wanted a chance to vote down the project through a ballot measure.

It’s no secret that public funds into training police in urban warfare will not serve public safety. Cop City is an invitation for corporations and investors to see Atlanta as an attractive hub, a city with its own mini city for training defenders of private property. Greater funding and more training for police has not led to fewer police killings and less racist police violence. As Atlanta community organizer Kamau Franklin noted in a rousing speech prior to Monday’s march, “In 2022, police killed more people than ever.”

“We Know Why We’re Here”

Organizers insist on seeing beyond the local: Protests like Monday’s are intended to invite out-of-state participants. The old and racist canard of “outside agitators,” peddled by Atlanta law enforcement and other officials since Stop Cop City began, falls flat against a locally led effort that wins national and international support.

“While there are hundreds of locals here, there are many who have come in solidarity,” Block Cop City organizer Sam Beard, an environmental activist from Chicago, told the assembled protesters on Monday. “We have descended into Atlanta because a call was made. And front-line activists in this struggle said, ‘We need your help.’ And we said, ‘We’ve got you.’”

The crowd roared with applause.

In an era of mass movements crushed swiftly and violently, the persistence of the fight for the Atlanta forest — even if relatively small in size — demands attention from those of us interested in forms of resilient resistance. It is consistent proof that anti-racist, environmental, Indigenous, and class-based battles can and must intersect.

Chants of “free, free Palestine” reverberating throughout the march made clear that Stop Cop City participants see their struggle over the forest acreage outside Atlanta as one among many fights to see land and territory liberated, rather than violently bordered and occupied.

“We’ve made the connections between the police, militarized complex, and international policing,” Franklin told the gathered crowd. “The murderous tactics of the Israeli police and military against the Palestinians. We’ve made those connections.”

Tortuguita’s father, Joel Paez, addressed the crowd, too, along with Belkis Terán, the late forest defender’s mother. “We know why we’re here.” Paez, who has regularly spoken out with fervor against Cop City since Tortuguita’s killing, told the protesters. “Do what you have to do.”

Within an hour of his speech, and within a mile of where his child was gunned down by police, cops beat slow-marching protesters and tear-gassed journalists.