This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

Nearly a century ago in Nicaragua, American Marines in an armed propeller plane spotted a group of civilian men chopping weeds and trimming trees far below. Convinced that something nefarious was underway, they opened fire. The U.S. never bothered to count the wounded and dead.

Four decades later in Vietnam, American troops hovering above a group of woodcutters grew unnerved when the men, women, and children failed to look up. Without provocation, the Americans unleashed rockets and machine-gun fire. Eight of the nine civilians below were killed.

For hours in 2021, Americans peered down at a man driving through the Afghan capital of Kabul and convinced themselves that he was a terrorist. They launched a missile that killed him and nine other civilians, including seven children.

In each instance, Americans displayed clear signs of confirmation bias, in which people seek information that reinforces their preexisting beliefs. The same failings contributed to a 2018 drone strike in Somalia that killed at least three, and possibly five, civilians, including 22-year-old Luul Dahir Mohamed and her 4-year-old daughter Mariam Shilow Muse.

Over the last century, the U.S. military has shown a consistent disregard for civilian lives. It has repeatedly cast or misidentified ordinary people as enemies; failed to investigate civilian harm allegations; excused casualties as regrettable but unavoidable; and failed to prevent their recurrence or to hold troops accountable. These long-standing practices stand in stark contrast to the U.S. government’s public campaigns to sell its wars as benign, its air campaigns as precise, its concern for civilians as overriding, and the deaths of innocent people as “tragic” anomalies. Such campaigns have mainly served to obscure the true toll of the American way of war, from the “banana wars” of the 1920s to the “forever wars” a century later.

A Stunning Reversal

Prior to World War II, the growing trend of “terror bombing” in conflicts across China, Ethiopia, and Spain outraged Americans. In 1937, President Franklin Roosevelt lamented that “without warning or justification of any kind, civilians, including vast numbers of women and children, are being ruthlessly murdered with bombs from the air.”

Soon after, however, the military embraced policies that put civilians at grave risk. During World War II, a British bombing raid on Dresden, Germany, created a firestorm that ripped through the city, suffocating and cooking people alive. A second British wave was followed by hundreds of U.S. bombers. All told, 25,000 to 35,000 people were incinerated. Confronted with “terror bombing” allegations after the attack, the head of U.S. Army Air Forces protested that war “must be destructive and to a certain extent inhuman and ruthless.” Roughly 600,000 German civilians were killed in air raids during the war.

In Japan, the U.S. attacked 67 cities, burning 180 square miles, killing more than 600,000 civilians, and leaving 8.5 million homeless. The massive death and destruction led Secretary of War Henry Stimson to worry that the United States would “get the reputation of outdoing Hitler in atrocities.” Nonetheless, Stimson signed off on an atomic strike on the city of Hiroshima that killed 140,000 people, mostly civilians, and another on Nagasaki, killing an estimated 70,000. The United States has never compensated those victims’ families or survivors of the attacks.

At war in Korea not long after, Gen. Douglas MacArthur declared that every city and village in the north was to be destroyed. And they were. Air Force Gen. Curtis LeMay later bragged that the U.S. had “killed off over a million civilian Koreans and drove several million more from their homes.”

The amount of ordnance dropped on Korea was dwarfed by the 30 billion pounds of munitions the U.S. expended in Southeast Asia during the 1960s and 1970s. Years before the war’s end, South Vietnam was already pockmarked with an estimated 21 million craters, some more than 20 feet across. In neighboring Cambodia, between 1969 and 1973, U.S. attacks killed as many as 150,000 civilians. The United States also pounded tiny Laos with more than 2 million tons of munitions, making it, per capita, the most heavily bombed country in history.

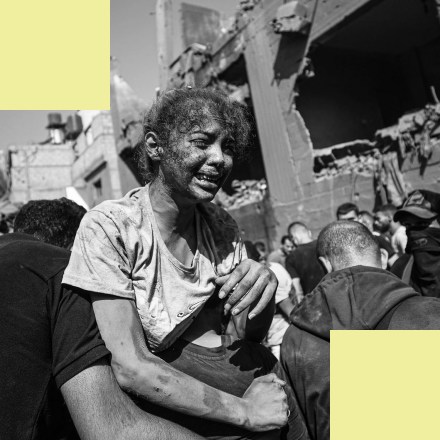

Key elements of America’s destructive brand of air war echo into the present. In recent weeks, Israeli officials have repeatedly justified attacks on Gaza by citing methods employed by the United States and its allies against Germany and other Axis powers during World War II. The United Nations has said “there is already clear evidence that war crimes may have been committed” by the Israeli military and Hamas militants. Israel has also embraced the use of “free-fire zones” — which the U.S. employed to open wide swaths of South Vietnam to almost unrestrained attack, killing countless civilians — in Gaza.

“We Didn’t Have All the Information”

A strike cell analyst who watched live video feeds from drones and helped make decisions about airstrikes offered The Intercept unprecedented insights about the U.S. air war in Somalia. He explained that, as Americans watch targets from the sky, a series of “wickets” — such as the absence of civilians or a potential target seen associating with a “known bad guy” — must be achieved before launching a strike. “When I was in Afghanistan, you normally had to hit five wickets, and in Africa, these ‘wickets’ were lessened,” he said. “I never really figured out what was a go or no-go in Somalia. It seemed to be all over the place. We often didn’t have all the information that we should have had to conduct a strike.”

The U.S. military employs MQ-9 Reaper drones, like the one pictured above, to conduct strikes against high-value targets in Somalia and elsewhere around the world. Attacks by these drones have also killed an unknown number of civilians.

When the strike cell analyst counted the civilians he knew the U.S. had killed and compared that tally with publicly announced figures, he said, “the numbers just didn’t add up.” Once, he recalled, the commandos he worked with pressured him to conduct a drone strike he was sure would endanger civilians. He refused to label the people he saw “adult-age males,” which would have allowed an air attack, he said. That forced them to conduct a ground operation against members of the terror group al-Shabab and saved some lives, but not all. “We knew that we killed two al-Shabab, but we also knew that we killed civilians,” he said, having watched video of the mission in real-time. “And nothing happened with that at all. I was really shocked by that. I thought we were going to be put under investigation, and I was going to have to go before some type of board. But nothing came of it.”

During the first 20 years of the war on terror, the U.S. conducted more than 91,000 airstrikes across seven major conflict zones — Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen — and killed up to 48,308 civilians, according to a 2021 analysis by Airwars, a U.K.-based airstrike monitoring group.

A 2020 study of post-9/11 civilian casualty incidents found most have gone uninvestigated. When they do come under official scrutiny, American military witnesses are interviewed while civilians — victims, survivors, family members — are almost totally ignored, “severely compromising the effectiveness of investigations,” according to the Center for Civilians in Conflict and Columbia Law School’s Human Rights Institute. That was the case with the 2018 Somalia strike that killed Luul and her daughter Mariam.

“It is unacceptable that in this strike and so many others, civilian survivors and families continue to struggle to get any kind of acknowledgment from the United States. The Department of Defense should urgently make long-overdue amends in consultation with the family,” said Annie Shiel, CIVIC’s U.S. advocacy director. “The family and the public at large also deserve transparency into the basis for this strike in the first place and how and why it resulted in the horrific deaths of a civilian mother and her young child.”