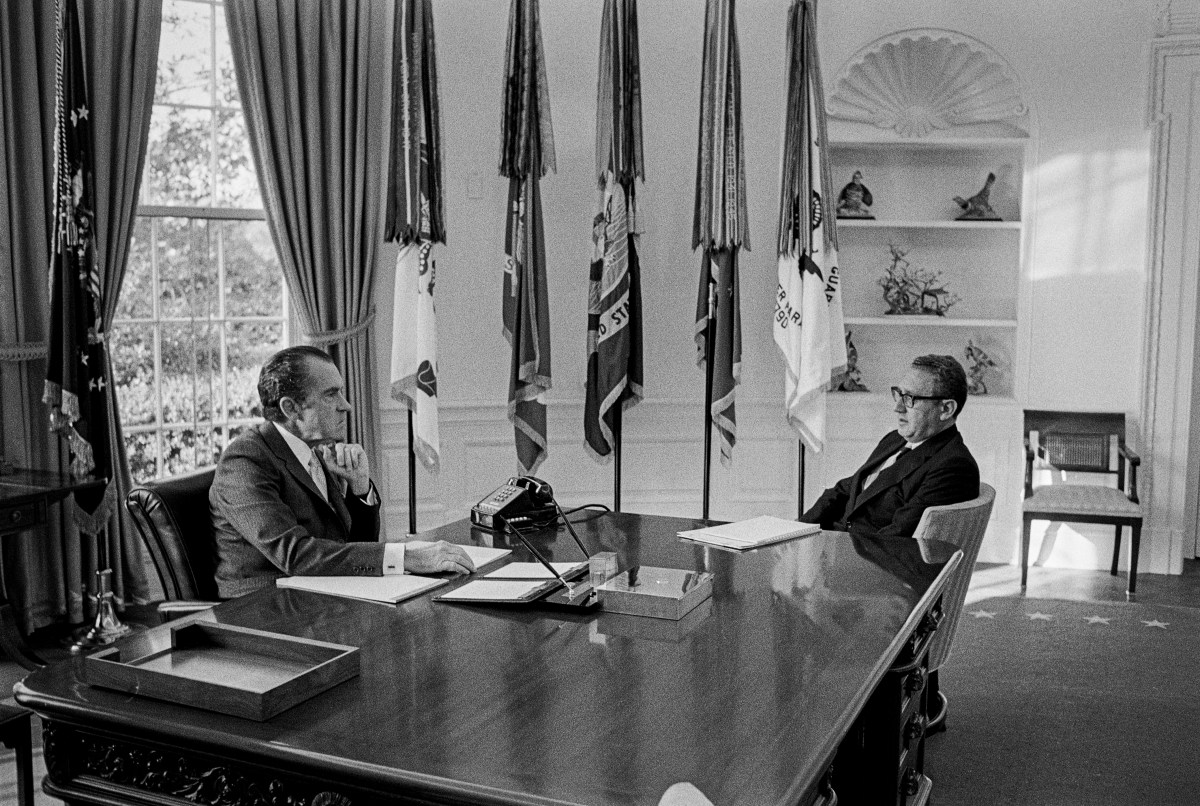

President Richard Nixon was in rare form, though in reality, it was none too rare. “The whole goddamn Air Force over there farting around doing nothing,” he barked at his national security adviser Henry Kissinger during a phone call on December 9, 1970. He called for a huge increase in attacks in Cambodia. “I want it done!! Get them off their ass and get them to work now.”

As Nixon rambled and ranted — calling for more strikes by bombers and helicopter gunships — Kissinger’s replies were short and clipped: “Right.” “Exactly.” “Absolutely, right.” We know this because, while Nixon was fuming about “assholes” who said there was a “crisis in Cambodia,” the conversation was being recorded. It wasn’t the secret White House taping system that finally laid Nixon low as part of the scandal that came to be known as Watergate, but Kissinger’s own clandestine eavesdropping system. Later, it was up to Kissinger’s secretary Judy Johnson to transcribe that night’s exchange and add in the single, double, triple, and even quadruple exclamation points to capture the spirit of the call and accurately punctuate the president’s words.

Johnson was new on the job when she heard the December 9, 1970, exchange. She was just one of many Kissinger secretaries and aides who, during his years working for the White House, either listened in on an extension and transcribed conversations in shorthand or typed up the transcripts later from Kissinger’s own Dictabelt recording system that, according to Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s 1976 book “The Final Days,” was hooked up to a telephone “housed in the credenza behind his secretary’s desk and … automatically activated when the telephone receiver was picked up.”

The transcripts offer a window into policymaking in the Nixon White House, Kissinger’s key role, and how so many Cambodians came to be killed by American military aircraft. Johnson was somewhat reluctant to talk about them and expressed surprise that they were publicly available.

Decades later, the heated December 1970 exchange didn’t stick out in Johnson’s mind, she told The Intercept. None of their conversations did. It was a long time ago and, she said, “there was a lot of stuff going on” at the White House. Johnson didn’t know whether Nixon was aware of Kissinger’s eavesdropping activities or why her boss recorded all his calls. Ask him yourself, she said. When I tried to interview him, Kissinger stormed off and his staff ignored follow-up requests for more than a decade. Johnson also cautioned that it was very hard to get an accurate sense of a conversation from the transcripts alone. There were nuances, she said, that were missing.

“Those conversations were strenuously edited,” said Roger Morris, a Kissinger aide who resigned in protest of the U.S. invasion of Cambodia in 1970 and had listened to many conversations between Nixon and his national security adviser. The men and women who took down the text didn’t completely eliminate the spirit of the conversations, but if you were listening to calls in their raw, original form, it was more disconcerting. “It was worse because the words were slurred and you knew you had a drunk at the other end,” he said of Nixon.

Did Johnson suspect that Nixon had been drinking when he called to direct policy and give orders? “If I did, I wouldn’t tell you,” she said. Any evidence is apparently gone forever. In a 1999 letter to Foreign Affairs, Kissinger claimed that the tapes of phone calls made in his office were destroyed after being transcribed. No notes or other materials involved in the transcription survived either, according to a 2004 report by the Nixon Presidential Materials Staff of the U.S. National Archives.

Johnson joined Kissinger’s staff in late 1970, before moving on to the White House press office in 1971 where she stayed until Nixon’s resignation in 1974. After a brief stint in the administration of President Gerald Ford, she moved to California and worked as a researcher for Nixon, who was then writing his memoirs. She might have been starry-eyed when she first arrived at the White House, she told me, but listening in on high-level phone conversations quickly disabused her of the notion that these were “super people.” She termed Nixon’s coarse talk “typical male language.”

Johnson took down Kissinger’s conversations using shorthand, she told me, repeatedly emphasizing how difficult it was to transcribe conversations like these perfectly. A “shit” or a “damn” might go missing, but there was no deliberate censorship and nothing was sanitized, she said. Morris recalled it differently. While Nixon’s remarks might be prettied up, he told me, it was Kissinger’s own acid-tongued ripostes that subordinates were supposed to excise to protect their boss. Privately, Kissinger called Nixon a madman, said he had a “meatball mind,” and referred to him as “our drunken friend.”

“I just had a call from our friend,” Kissinger told his aide Alexander Haig moments after getting off the phone with Nixon on that December night, according to Johnson’s transcript. The president “wants a massive bombing campaign in Cambodia,” Kissinger told Haig. “He doesn’t want to hear anything. It’s an order, it’s to be done. Anything that flies on anything that moves. You got that?” In a notation, Johnson indicated that while it was difficult to hear him, it sounded as if Haig started laughing.

When I mentioned these orders and asked about Nixon’s drinking, Johnson emphasized that there were buffers in place. Policy changes, she told me, weren’t as simple as a presidential order given by phone. Many discussions would occur before instructions were carried out. But Kissinger’s immediate and blunt relay of Nixon’s command suggests otherwise. The raw number of U.S. attacks in Cambodia does too. While they had no explanation for it at the time, The Associated Press found that compared with November 1970, the number of sorties by U.S. gunships and bombers in Cambodia had tripled by the end of December to nearly 1,700.

Was the reason for it — and the Cambodian deaths that resulted — a drunken president’s order, passed along swiftly and unquestioningly by Henry Kissinger? Nixon and Haig have been dead for many years, and Johnson passed away earlier this month. That leaves only Kissinger to answer the question — and to answer for the deaths.