In September 1966, two U.S. helicopters crossed the border of South Vietnam and flew 20 miles into the neutral kingdom of Cambodia. Near the town of Snuol, they blasted a Cambodian army outpost with eight rockets, killing one soldier and wounding four others. The air assault was blamed on “pilot error,” and it was just one of many lethal U.S. helicopter attacks in Cambodia during the Vietnam War. Three and a half years after the errant airstrike, U.S. forces would again attack Snuol, but this time it was no mistake. Instead, U.S. troops deliberately assaulted the town as part of America’s “Cambodian incursion,” an ill-fated invasion that President Richard Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, hoped would win the Vietnam War.

A previously unrevealed military investigation — declassified in the 1980s but buried deep in the files of Vietnam War-era inspector general’s documents in the nation’s archives — shows that after U.S. soldiers were caught looting Snuol in May 1970, the Army launched a pro forma investigation, worked to minimize the story, and even tried to blame the press corps for sacking the town. The Army, however, never questioned its own reporter on the scene: a journalist working for the venerable U.S. military newspaper Stars and Stripes. In an interview with The Intercept, he laughed at the notion that journalists had looted Snuol.

The Snuol revelations are part of an exclusive archive of U.S. military documents assembled by The Intercept as part of a reflection on the life and crimes of Henry Kissinger, who will turn 100 on Saturday.

Kissinger, the architect of America’s 1969 to 1973 bombing of Cambodia and a proponent of the 1970 invasion, acknowledged that 50,000 Cambodian civilians were killed during his tenure crafting America’s war policy. Experts have conservatively estimated the actual total may be three times higher.

The Sack of Snuol

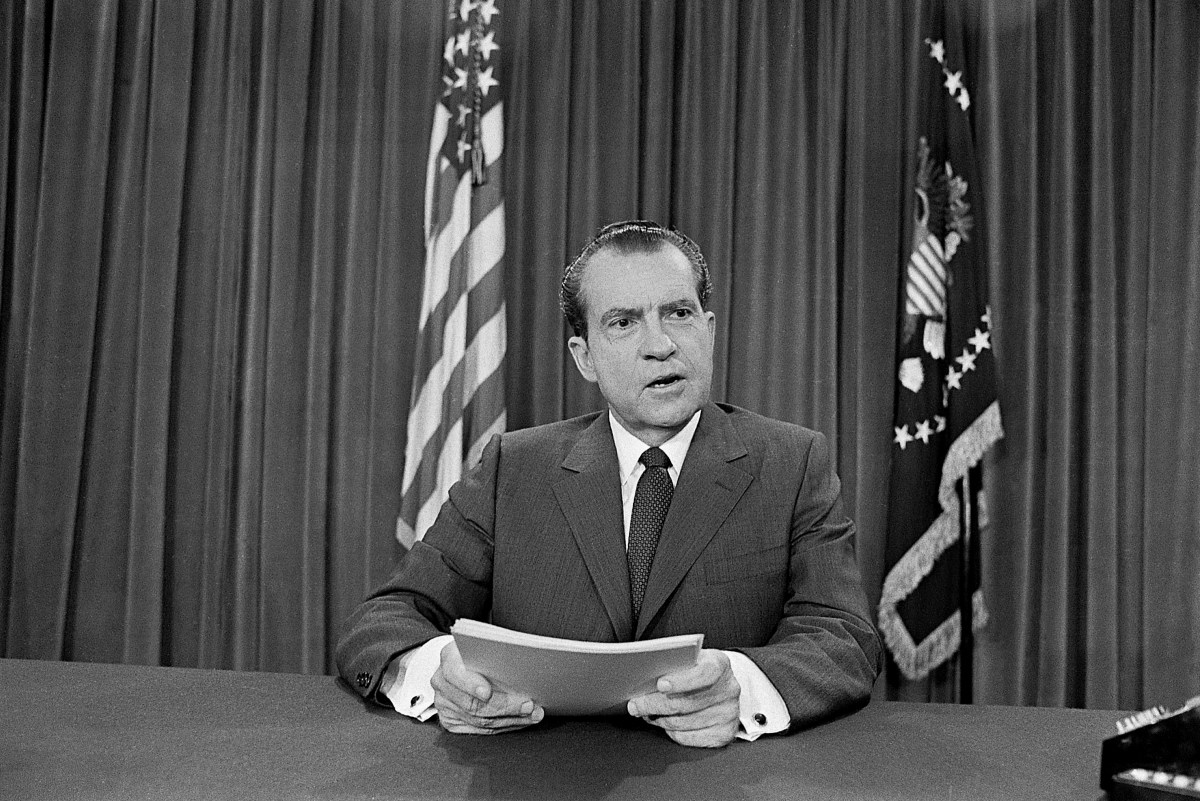

On April 28, 1970, Nixon issued an order that was opposed by his secretary of state and secretary of defense but endorsed by Kissinger: The U.S. military would invade Cambodia. Two days later, in a televised address to the nation, Nixon announced the assault and offered a history lesson loaded with lies. Since 1954, when an international agreement formally ended a U.S.-backed French war to maintain their colonies in Indochina, he said, U.S. policy had been “to scrupulously respect the neutrality of the Cambodian people.” His statement belied the covert cross-border missions and secret bombings being carried out — and hidden from the American public and Congress — on his orders throughout the previous year. “In cooperation with the armed forces of South Vietnam, attacks are being launched this week to clean out major enemy sanctuaries on the Cambodian-Vietnam border,” he continued. “This is not an invasion of Cambodia. … Our purpose is not to occupy the areas. Once enemy forces are driven out of these sanctuaries and once their military supplies are destroyed, we will withdraw.”

U.S. troops and armored vehicles streamed across the border but encountered few enemy soldiers and saw little pitched combat. Kissinger had “no doubt about the operation’s success” and publicly described it as a victory, but the CIA later determined that the capability of enemy forces in Cambodia had not been “substantially reduced,” while the National Security Agency deemed the invasion an “unmitigated disaster.”

Four Kissinger staffers resigned over their boss’s role in planning the invasion, arguing that it would achieve none of its objectives and lead to “blood in the streets” at home. They were right. As predicted, the “incursion” sparked widespread campus unrest across America, including at Kent State University, where members of the Ohio National Guard killed four students during a protest a few days later.

A week after the killings at Kent State, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover rushed Nixon and Kissinger a report on the private phone conversations of Morton Halperin, a Kissinger protégé and national security aide whose home phone Kissinger had ordered tapped. According to an FBI transcript, Halperin predicted that the “most certain consequence” of the invasion would be “that a large number of Cambodian civilians would be killed and labeled Viet Cong.” He, too, was right.

As U.S. troops plowed through the countryside, the 2nd Squadron, 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment was tasked with taking the town of Snuol. According to Army documents, Brig. Gen. Robert M. Shoemaker ordered that minor resistance should not necessitate the town’s destruction. “Try to avoid shooting into crowds of civilians,” his subordinate Lt. Col. Grail Brookshire, the commander of the 2nd Squadron, 11th Cavalry Regiment, told his men on the outskirts of the town, according to an account from New York Times reporter James Sterba, who was there to cover the battle. “In other words, if you’re taking light fire and there are civilians in the area, try to return the fire without losing all the fuckin’ civilians.” In a recent conversation with The Intercept, Brookshire emphasized that when his forces encountered a mixed group of North Vietnamese troops and “Cambodian refugees,” he would not allow his men to open fire on them.

When they encountered enemy resistance as they entered Snuol, Brookshire nonetheless ordered his tanks to turn their guns on the town and called in bombers and helicopter gunships, leveling buildings to dislodge North Vietnamese forces. The next day, Brookshire’s men moved fully into Snuol.

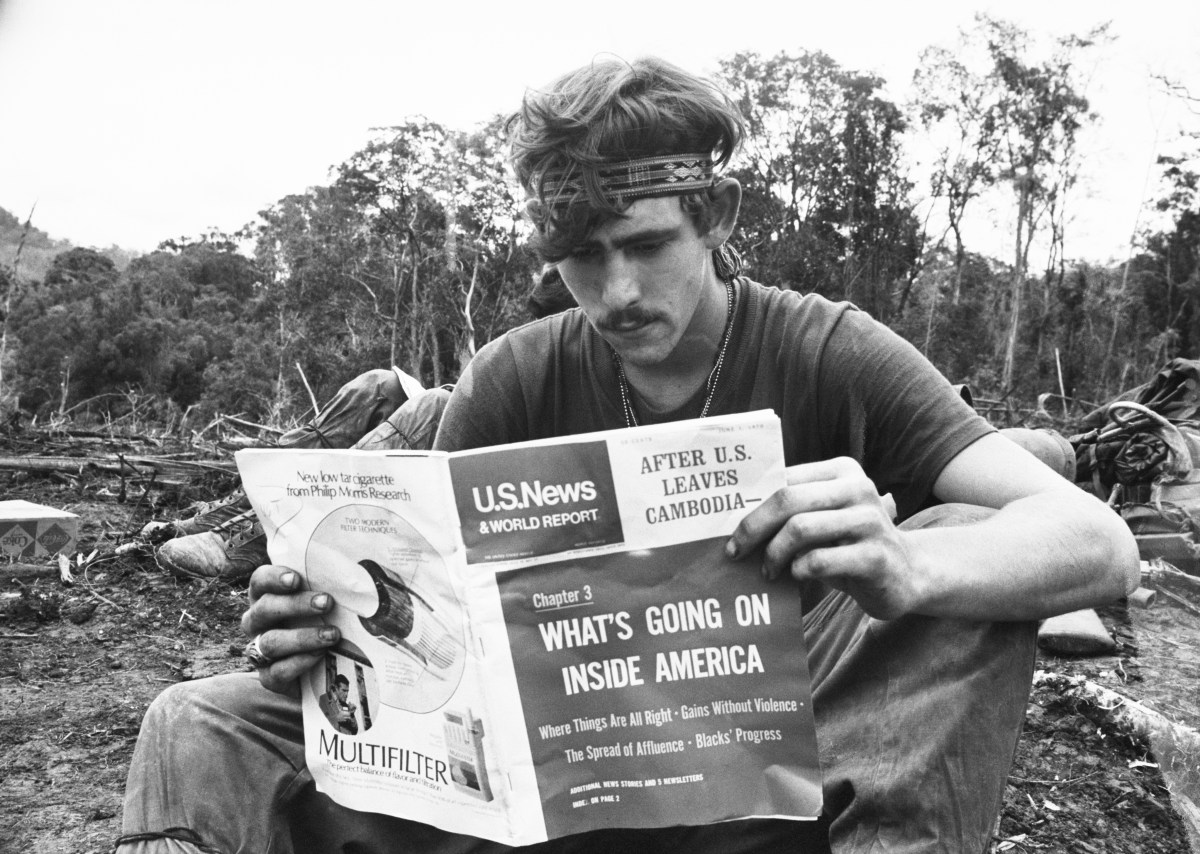

While it was a major battle in the U.S. incursion into Cambodia, the invasion of Snuol wasn’t significant in terms of the wider war in Indochina. Taking the town did not cost a single American life and left only five U.S. troops wounded. Leon Daniel, a former Marine and Korean War veteran who covered the operation for United Press International, rode into Snuol on one of the Army’s tanks. “The only dead I saw were obviously Cambodian civilians, but the U.S. Army claimed later it had killed 88 Communist troops in the area,” he wrote. “I doubt it.” All told, he saw four dead: a little girl and people he assumed were her family. They had all been killed by napalm. He also watched U.S. soldiers

helping themselves to what little was left in an area of shops that had been destroyed. The first items taken were beer and soft drinks because it was very hot. Other GIs took suitcases, mirrors and shoes. I saw a motorscooter strapped to one tank. … Other soldiers broke locks off a few sheds that were still standing. One shed was set on fire after it was looted of several cases of batteries.

Associated Press reporter Peter Arnett described soldiers smashing open the doors of shops to steal watches, clocks, and other items before setting the stores ablaze. “I saw one soldier run from a burning Chinese noodle shop with his arms full of Cambodian brandy … and two others wheeled out motorcycles and tied them to the turrets of their vehicles,” he recalled in his 1994 memoir “Live From the Battlefield.” “After about an hour of looting and merrymaking an officer came by and yelled, ‘Get your hands off that stuff, we’re moving on.’ The soldiers laughed and mounted their vehicles.”

Looting or Lies?

While Arnett’s dispatch from Snuol was published in its entirety around the world, the versions carried by American news organizations were missing a critical piece of reportage: any mention of the looting. The AP had decided, in the wake of the killings at Kent State, to censor the story. “Let’s play it cool,” Ben Bassett, the late, longtime foreign news editor of The Associated Press wrote in a cable to the AP bureau in Saigon, explaining that “in present context [mention of the looting] can be inflammatory.”

With the AP’s Saigon staff up in arms, Arnett fired off a message to the home office. “I was professionally insulted by New York’s decision to kill all my story and picture references to the Snuol looting on grounds that it was inflammatory and not news,” he wrote, recounting the cable in his memoir. “To ignore the sordid aspects of America’s invasion of Cambodia would surely be a dereliction of a reporter’s duty and I find it impossible now to continue to compromise my reporting to suit American political interests.” Arnett, who had previously won a Pulitzer Prize for his coverage of the war in Vietnam, then leaked the story of AP’s censorship to Kevin Buckley of Newsweek, who had also reported from Snuol.

With the press and Congress demanding answers, the Army launched a cursory investigation into “the extent of damage… and the veracity of news accounts” about U.S. troops’ role in the looting, according to the formerly classified Army records.

“My soldiers haven’t been looting,” Brookshire had told a TV crew. But footage showed otherwise. A soldier was filmed handing bottles to a colleague on a tank who said, “If you find any more sodas, get ’em.” Another was seen pilfering a radio. Still another was caught rooting through a shed.

“I don’t know what kind of Scotch it was because the label was in Cambodian,” one of Brookshire’s men told Gloria Emerson of the Times, “but it wasn’t bad at all.” As civilians drifted back into Snuol, they found a sea of debris: shattered glass, burned bicycles, twisted metal, and busted bricks, amid huge craters that had swallowed up homes and shops. “We want no shooting or killings by anyone here, and look what has befallen us,” one resident told Emerson. “We just want to earn our living.”

Blaming the Messengers

In June 1970, the Army concluded its investigation into the sack of Snuol. About half the structures in Snuol were “destroyed or damaged” by U.S. bombs, napalm, tank rounds, and small arms fire, according to an inspector general’s report. The Army also discovered more dead Cambodians than reporters had seen, noting that troops found 11 bodies “presumed to be civilians.”

“Reports of looting and pillage are confirmed by statements in the file,” a follow-up report by an Army staff judge advocate noted. That report corroborated accounts of soldiers stealing a “motorbike, cases of soft drinks, sunglasses and razor blades,” while disputing reports that GIs pilfered Cambodian currency, beer, and other items.

The staff judge advocate’s report stated that there was “no evidence of a general rampage through undestroyed shops” and raised an alternate theory about the looting: Any theft “was done by civilian reporters in their wandering about the village.”

The Times’s Sterba never made it into Snuol, and Newsweek’s Buckley said that he left before the looting occurred. Gloria Emerson and Leon Daniel died in 2004 and 2006, respectively. However, The Intercept spoke with one reporter on the scene who should have been first on the Army’s witness list.

While the Army’s investigation failed to mention it, the military’s own newspaper, Stars and Stripes, had a reporter in Snuol. Army Specialist Jack Fuller — who went on to win a Pulitzer in 1986 and serve as editor and publisher of the Chicago Tribune and president of the Tribune Publishing before his death in 2016 — rode into Snuol atop one of Brookshire’s tanks. He watched as 11th Cavalry troops began stealing radios, soft drinks, and alcohol.

“I knew it was a story,” he told The Intercept in a 2010 interview, speaking of his article, which included an account of GIs pillaging the town. “Looting of any dimension by American soldiers was a story for Stars and Stripes, in my view.”

Fuller laughed out loud when I read him the staff judge advocate’s conjecture about the civilian press looting the town. “I certainly saw no correspondents grabbing anything,” he said, noting that, unlike soldiers, members of the media had easy access to alcohol and no need to steal it.

Fuller recalled running into Arnett after the flap with AP. “He said: ‘For god’s sake, AP kills my story and Stars and Stripes runs yours. Stripes has more courage than AP,’” Fuller told me, noting that he had mentioned the looting deep in his story, while Arnett reported it more prominently in his article.

Arnett did not respond to email inquiries to be interviewed for this story.

The Butcher of Snuol

In June 1970, an Army spokesperson announced that the looting in Snuol was limited to “several, perhaps five or six, cases of soda pop, which were consumed.” A motorcycle that was taken had been returned to its owner, the Army said, and a tractor would be returned once its owner was located.

No mention was made of the theory that the press had pillaged Snuol.

The two-month Cambodian incursion left 344 American soldiers and 818 South Vietnamese troops dead. There were, however, “no reliable or comprehensive” statistics for Cambodian civilian casualties, although the Pentagon estimated that the operation rendered 130,000 Cambodians homeless. The invasion proved only a minor inconvenience for North Vietnamese forces in Cambodia. By the end of June 1970, most U.S. troops had left the country, and the North Vietnamese soldiers had moved back into the region around Snuol. By late October, America’s South Vietnamese allies were fighting their way back into the town.

Grail Brookshire did, however, get something out of the incursion. His troops’ looting of Snuol became a joke — and Brookshire gave himself a grisly, though tongue-in-cheek, nickname.

In a conversation this month, Brookshire defended his troops and told The Intercept that they “got a bum rap” from reporters. He expressed a low regard for the press, then and now, and a belief that they are “part of the deep state.”

In 1972, having recently returned from four years’ reporting in Southeast Asia, Buckley gave a talk at the U.S. Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island, during which a man in the back asked numerous well-informed questions. “He and others swarmed me when the event was over — and I asked him his name and where he had been,” Buckley told The Intercept.

“Grail Brookshire,” the man responded.

“You mean —” Buckley began, but before he could finish the sentence, the man interrupted.

“That’s me, Grail Brookshire, the Butcher of Snuol,” he told Buckley. (When we spoke recently, Brookshire didn’t recall the particulars of this exchange from 51 years ago, but said it sounded like the type of “smart-ass remark” he would make.)

“You guys said my troops systematically looted the place,” Brookshire told Buckley. “My god, my men couldn’t do anything systematically.”