Ny Sarim had lived through it all. Violence. Loss. Privation. Genocide.

Her first husband was killed after Pol Pot’s murderous Khmer Rouge plunged Cambodia into a nightmare campaign of overwork, hunger, and murder that killed around 2 million people from 1975 to 1979. Four other family members died too — some of starvation, others by execution.

“No one ever even had time to laugh. Life was so sad and hopeless,” she told The Intercept. It was enough suffering for a lifetime, but it couldn’t erase the memory of the night in August 1973 when her town became a charnel house.

Ny was sleeping at home when the bombs started dropping on Neak Luong, 30 tons all at once. She had felt the ground tremble from nearby bombings in the past, but this strike by a massive B-52 Stratofortress aircraft hit the town squarely. “Not only did my house shake, but the earth shook,” she told The Intercept. “Those bombs were from the B-52s.” Many in the downtown market area where she worked during the day were killed or wounded. “Three of my relatives — an uncle and two nephews — were killed by the B-52 bombing,” she said.

The strike on Neak Luong may have killed more Cambodians than any bombing of the American war, but it was only a small part of a devastating yearslong air campaign in that country. As Elizabeth Becker, who covered the conflict as a correspondent for the Washington Post, notes in her book “When the War Was Over,” the United States dropped more than 257,000 tons of explosives on the Cambodian countryside in 1973, about half the total dropped on Japan during all of World War II.

“They caused the largest number of civilian casualties because they were bombing so massively with very poor maps and spotty intelligence.”

“The biggest mistakes were in 1973,” she told The Intercept. “They caused the largest number of civilian casualties because they were bombing so massively with very poor maps and spotty intelligence. During those months ‘precision bombing’ was an oxymoron.” Neak Luong, she concurred, was the worst American “mistake.”

State Department documents, declassified in 2005 but largely ignored, show that the death toll at Neak Luong may have been far worse than was publicly reported at the time, and that the real toll was purposefully withheld by the U.S. government.

In his 2003 book “Ending the Vietnam War,” Henry Kissinger wrote that “more than a hundred civilians were killed” in the town. But U.S. records of “solatium” payments — money given to survivors as an expression of regret — indicate that more than 270 Cambodians were killed and hundreds more were wounded in Neak Luong. State Department documents also show that the U.S. paid only about half the sum promised to survivors.

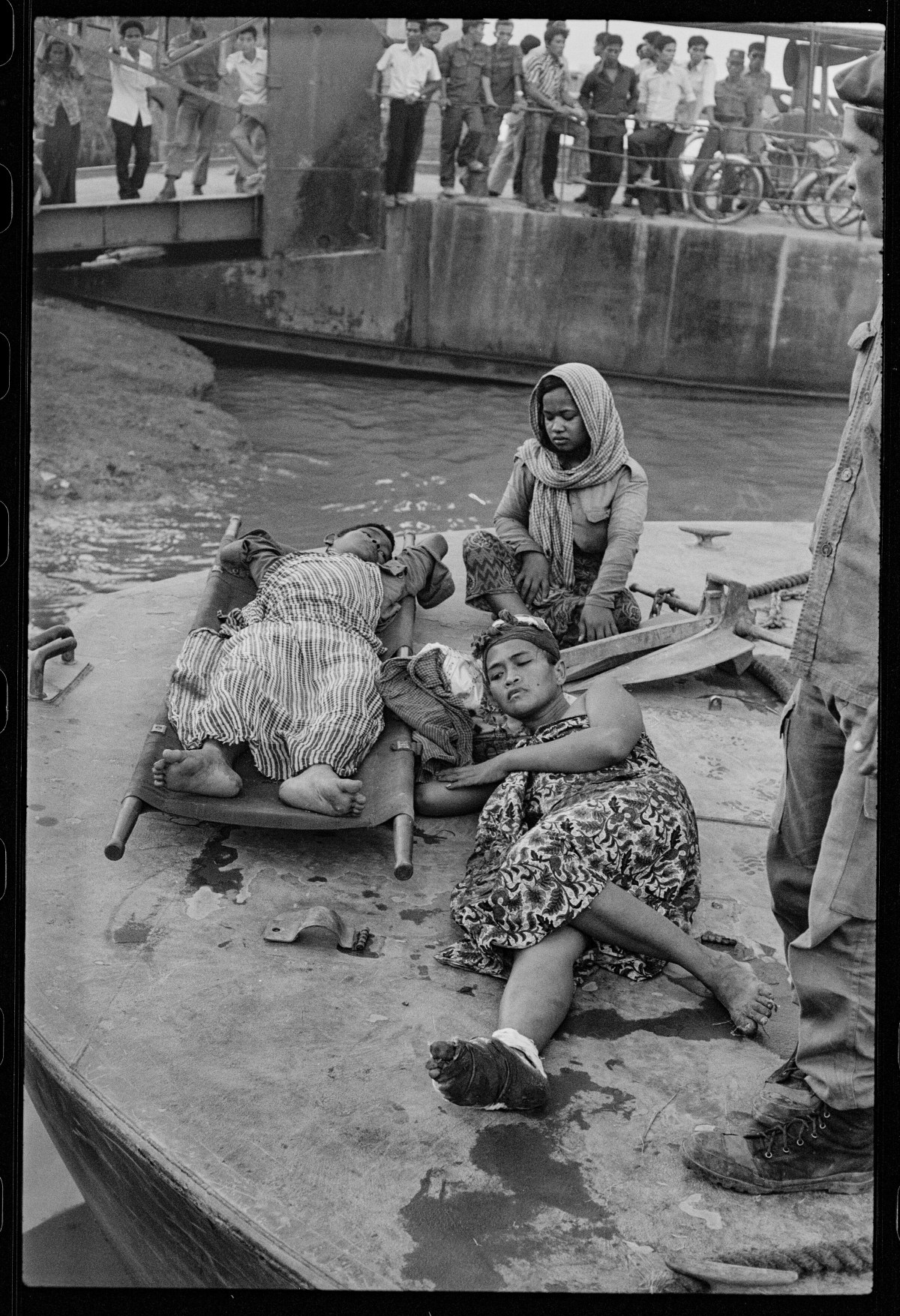

Cambodian civilians wounded by a U.S. warplane at Neak Luong on August 6, await transportation to hospital on Aug. 7, 1973.

The Price of a Life

The death warrant for Neak Luong was signed when U.S. officials decided that American lives mattered more than Cambodian ones. Until 1967, U.S. forces in South Vietnam used ground beacons that emitted high frequency radio waves to direct airstrikes. But the U.S. stopped using the beacons after a radar navigator on a B-52 bomber failed to flip an offset switch, causing a bomb load to drop directly on a helicopter carrying a beacon instead of a nearby site designated for attack. The chopper was blown out of the sky, and the U.S. military switched to a more reliable radar system until the January 1973 ceasefire formally ended the U.S. war in Vietnam.

At that point, the more sophisticated radar equipment went home, and the less reliable ground beacons came into use in Cambodia, where the U.S. air war raged with growing intensity.

In April 1973, according to a formerly classified U.S. military history, American officials expressed concern that “radar beacons were located on the American Embassy in Phnom Penh” and raised “the possibility that weapons could be released in the direct mode,” striking the U.S. mission by accident. Within days, that beacon was removed. But while Americans at the embassy were safe, Cambodians in places like Neak Luong, where a beacon had been placed on a pole in the center of town, remained at risk. “It should have been put a mile or so away in the boondocks,” a senior U.S. Air Force officer told the New York Times in 1973.

On August 7, 1973, a secret cable shot from the beacon-less U.S. Embassy in Phnom Penh to the secretaries of State and Defense and other top American officials in Washington. At approximately 4:35 a.m. in Cambodia, according to Deputy Chief of Mission Thomas Enders’s message, Neak Luong was “accidentally bombed by a yet undetermined [U.S. Air Force] aircraft.”

Ny said that her cousin, who served with the U.S.-allied Cambodian army and spoke English, got on the radio shortly after the bombing and asked an American what had happened. He was told that the bombs were dropped in error, she said.

It later became clear that a navigator had again failed to flip the offset bombing switch.

“No Great Disaster”

Col. David Opfer, the U.S. Embassy’s air attaché, quickly flew to the town to survey the situation, he told The Intercept. “I remember that some of the injured people were very happy to see somebody arrive, and I sent some of the most seriously wounded people back to the hospital in Phnom Penh in my helicopter,” he said. (Opfer died in 2018.)

Opfer told the foreign press corps in Phnom Penh that the bombing was “no great disaster.”

“The destruction was minimal,” he announced at a press briefing, even though Enders, in the secret cable, had already informed U.S. officials that damage was “considerable.”

In a November 2010 interview, Opfer reiterated that he didn’t consider the damage to Neak Luong significant, and that it was limited to a small area. “It was a mistake,” he explained. “It happens in war.”

Sydney Schanberg, who reported for the New York Times in Cambodia, recalled Opfer’s briefing. “He said the casualties weren’t severe,” Schanberg, who died in 2016, told The Intercept. “He said there were 50 dead and some injured.” Opfer admitted that he didn’t actually know the number. “Even then I wasn’t sure how many,” he told The Intercept.

Schanberg, who later won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting from Cambodia, was skeptical of the pronouncement and set out to see for himself. He was thrown off a Cambodian military flight to Neak Luong, but Schanberg’s fixer Dith Pran got them to the town by boat, and they interviewed survivors until local officials detained the journalists for taking photographs of “military secrets.” The U.S. Embassy, meanwhile, tried to wrest control of the story by arranging for a group of five Western reporters to take a quick look around with little opportunity to speak to townspeople.

Schanberg and Pran, who spent a day and night under house arrest, watched their press colleagues through the window of the building where they were confined. “They didn’t see enough to write a detailed story and they hadn’t talked to anybody,” said Schanberg, noting that the pool reporters were only on the ground for about 20 minutes.

Ny Sarim told The Intercept that soldiers from the U.S.-allied Cambodian military also kept residents from making their way downtown, but that even from a distance, the damage was unmistakable. When she finally got through the cordon, she saw massive craters and twisted metal. “It was a total wreck,” Schanberg told me. “Everything had been hit.”

Schanberg’s August 9, 1973, front-page Times story on Neak Luong emphasized Opfer’s minimization of the damage; a second article and an editorial soon after detailed U.S. efforts to thwart Schanberg from covering the story.

In a confidential cable back to Washington, U.S. Ambassador Emory Swank mentioned “the New York Times correspondent’s accusation that the air attaché office attempted to block journalists’ access to Neak Luong” and defended the officer. “Colonel Opfer has done well in trying circumstances,” he stated, while casting the foreign press corps as “demanding and hostile.” Opfer told The Intercept that the Cambodian military had detained Schanberg and Pran. “They always get things mixed up and don’t tell it as it really is,” he said of the press.

Schanberg took a different view. Opfer, he said, “was absolutely unskilled with the press. I felt bad for the man, in a way, because he was telling us what he had been told to tell us. A lot of the senior officers felt that we didn’t give anybody a fair break — but the Cambodians weren’t getting much of a break, were they?”

On Aug. 7, 1973, a day after being injured in the U.S. bombing of civilians in Neak Luong, a baby waits for transportation to the hospital.

A Grand Bargain

Officially, 137 Cambodians were killed in the Neak Luong bombing and 268 were wounded, according to the U.S. Embassy in Phnom Penh. Months later, Enders, in a confidential, December 1973 cable that went to Kissinger and then-Secretary of Defense James R. Schlesinger, confided that the U.S. had actually paid out solatium for 273 dead, 385 seriously wounded, 48 who suffered “mutilation,” and 46 victims of slight injuries. All told, that figure — 752 people hurt or killed — was 86 percent higher than the official number.

Enders stated that the U.S. had not sought to verify the numbers, but that the tally had been certified by the Cambodian regime. The final number of wounded and dead, he noted, “is higher than the official count given by [the Cambodian government] to the press and therefore should not be released.”

In the December 1973 cable, Enders admitted that the U.S. had never established a policy for “the payment of medical expenses for persons injured by U.S. errors,” and that the bombing of Neak Luong was “the only such incident which has occurred in Cambodia.” But just a day after the Neak Luong bombing, a State Department cable referenced a “second accidental bombing” at Chum Roeung village that killed four to eight people and injured up to 33. The Pentagon blamed the “error” on a F-111 bomber’s “faulty bomb-release racks.” By then, the U.S. had dropped hundreds of thousands of tons of bombs throughout the countryside and killed, according to experts, as many as 150,000 Cambodians.

Two weeks after the bombing of Neak Luong, Swank, the U.S. ambassador, publicly signed an agreement on compensation with the Cambodian government. “We desire to compensate, insofar as possible, the survivors of the tragedy,” he said in a brief speech, adding that the U.S. would pay $26,000 to rebuild the damaged hospital in Neak Luong and provide $71,000 in equipment.

The next of kin of those killed, according to press reports following his speech, would receive about $400 each. Considering that in many cases, the primary breadwinner had been lost for life, the sum was low: the equivalent of about four years of earnings for a rural Cambodian at the time. The financial penalty meted out to the B-52 navigator whose failure to flip the offset switch killed and wounded hundreds in Neak Luong was low too. He was fined $700 for the error. By comparison, a one-plane sortie, like that which bombed Neak Luong, cost about $48,000 at the time. A B-52 bomber cost about $8 million.

In another confidential cable sent in December 1973, Thomas Enders made a final accounting of solatium payments to those who had lost a relative in Neak Luong. They had actually not received the $400 per dead civilian that they had been promised. In the end, the U.S. valued the dead of Neak Luong at just $218 apiece.